Architects Herzog & de Meuron designed Pérez Art Museum Miami (PAMM) with few interstitial spaces and an emphasis on the interconnected nature of each gallery—allowing visitors to “surf” the museum. Their design encourages us to simultaneously conceive of the works in the museum as part of a broader whole while experiencing each singularly. In their rethinking of the possibilities and uses of museum spaces, Herzog & de Meuron also designed an unusually proportioned double-height gallery that extends an invitation to artists to experiment, to stretch the possibilities of both physical objects and sensory perceptions. For his newly commissioned project A C I D G E S T, London-based artist Haroon Mirza has done just that, creating a carefully calibrated experiment in sound, sight, and feeling for visitors to step into.

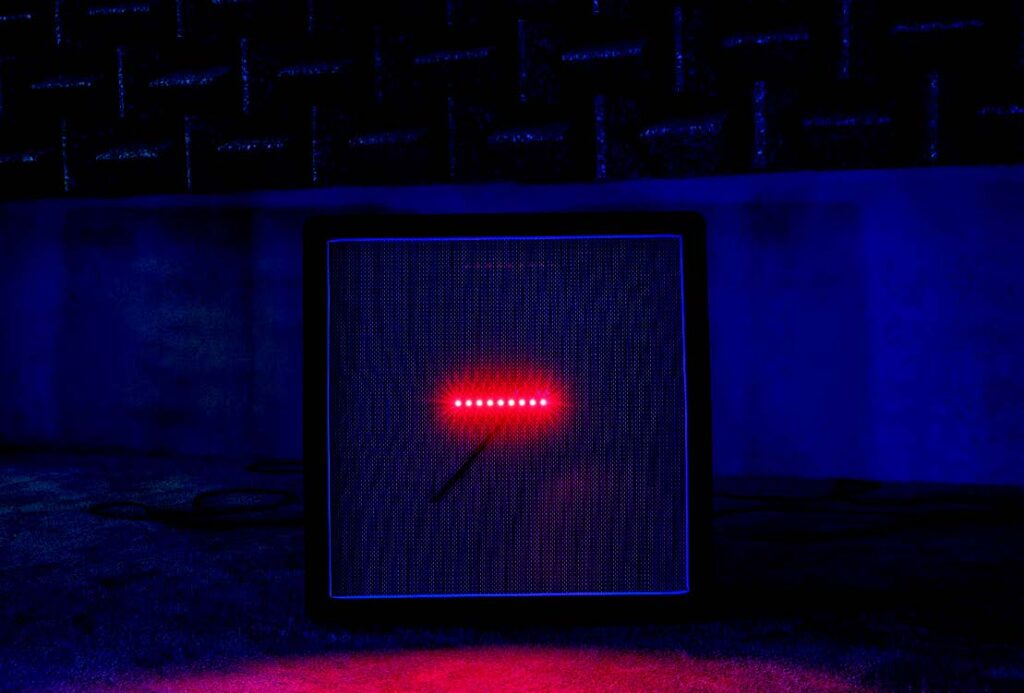

This gallery is one of a number of exaggerated or disproportionate architectural spaces Mirza has engaged recently. Here he responds to the space as an acoustic site, employing its expansive height to create distinct auditory phenomena. On the floor of the gallery Mirza has gathered a ring of Marshall cabinet speakers in a circular arrangement he uses frequently. Each speaker has been modified, its systems physically rewired and its surface affixed with strips of colored LED lights that cover the Marshall logo. The amplified sound of the electrical currents simultaneously powering the LEDs as they turn on and off emanate from each speaker. Each color corresponds to a different electrical frequency and thus a different tone and temporality; together they create an organic, nonmusical rhythm of buzzing, droning, and humming sounds, making audible what writer Emma Warren has referred to as the “hidden harmonics of random sound.”

The patterns of light and sound in A C I D G E S T are dictated by a text Mirza created that functions as a score for the piece. Within his practice, these compositional scores can take many forms and are created in response either to a network of ideas or to another artist’s practice, as in his recent project based on the work of artist Channa Horwitz (1932–2013). For A Chamber for Horwitz: Sonakinatography Transcriptions in Surround Sound (2015), Mirza transformed one of Horwitz’s intricately gridded, colored drawings into an immersive, animated sound and light installation. The work exemplifies Mirza’s exploration of how the formal patterns and logics of an artwork or text can be translated to other means of expression and perception.

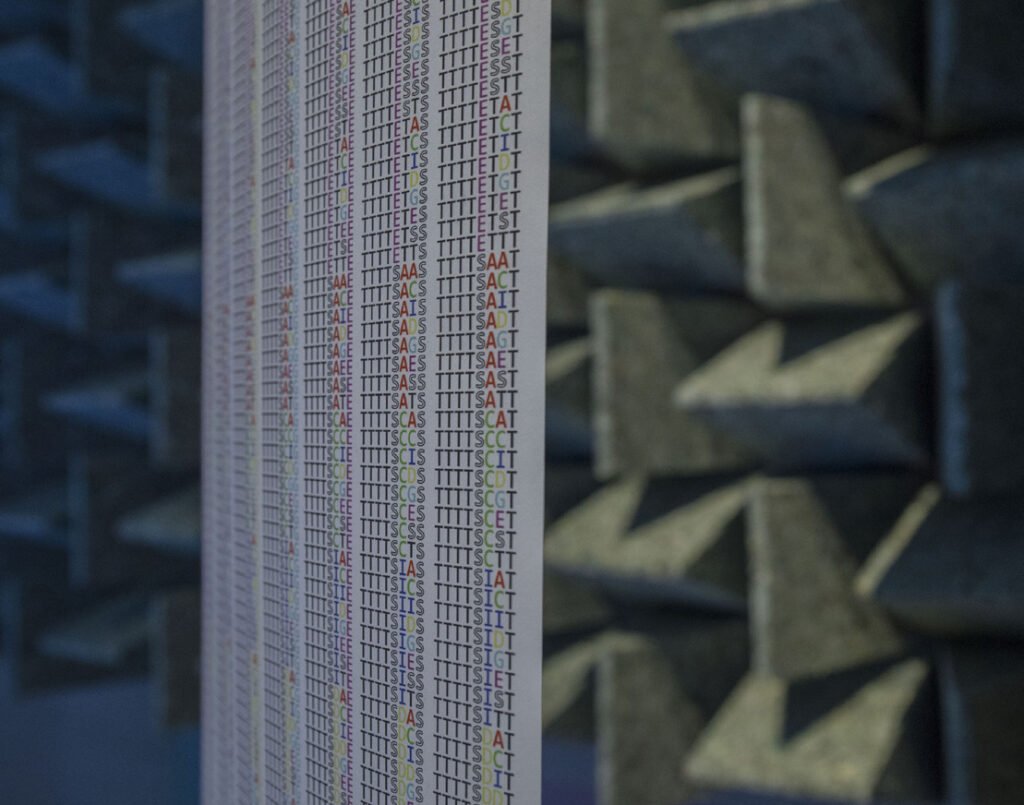

Mirza also used this approach for his project at PAMM, responding to the museum’s exceptional collection of concrete poetry—text-based artworks centered on the visuality of language, letters, typography, and composition—acquired from longtime Miami-based collectors Ruth and Marvin Sackner. Inspired in part by the work of French 20th-century poet and musician Henri Chopin (1922–2008), who used a typewriter to create repeating, all-over patterned compositions of letters and punctuation, Mirza made his own concrete poem, exploiting the implicitly acoustic qualities of this medium—as much as concrete poetry capitalizes on the visual qualities of text, it also invokes whatever sound and rhythm we understand from a piece as we “read” it in our minds.

Mirza used the word “acidgest” as the basis of his poem. This term is a play on “acid tests”—the name given to acid or LSD parties of the 1960s, and it conjures a world of hallucinogens and psychedelia. Mirza has replaced the first t with a g, a requirement of the programming system to avoid repetition, but also in reference to the ordering of nucleotides, the foundation of DNA, which are ascribed the letter codes of A, C, G, T. This seemingly nonsensical term—“acidgest”—has been transformed into a 16-million-line concrete poem created through computer programming. Matching each letter of the word to one of eight colors (red, green, blue, yellow, magenta, cyan, black, and white), the poem consists of every possible combination and order of these letters in eight-character lines. As the letters shift position along the grid of this text, the colors of each letter determine the light and sound emissions of each speaker, constituting a translation and materialization of Mirza’s poem. Each letter corresponds to one one-thousandth of a second, and it takes 18 days for the entire score to be played. The piece is set to play from the beginning on the first day of each month throughout the exhibition’s run.

The artist has compared the patterning of the letters to the reordering combination of nucleotides in the double helix of DNA and is interested in the interrelationship between DNA and psychedelia, and more broadly in the unseen patterns present in much of our lives, whether biological or mechanical, observed or imagined. Printed on a massive scroll and hung from the upper register of the gallery—not unlike the piano rolls of the late 19th century that bear a formal echo—the system of the poem dictates the entirety of the piece through patterned and repeated information.

Mirza has covered the gallery’s lower walls in a dense pattern of triangular pieces of rebonded, recycled foam.

Across several projects, Mirza has employed an aestheticized and industrialized version of this type of foam, which is used to create anechoic spaces (spaces free of echoes). The dense foam material and its crevassed surfaces, as well as the thick carpeting on the floor, absorb much of the reverberation coming from the speakers, creating a precise and controlled sound and a muted acoustic space. The upper tier of the gallery walls, however, has been left in its “natural state”—polished concrete—so that the sound travels and ricochets freely. While below, at human scale, we experience precise sounds emitted from the speakers, above us sound circulates in a loose and busy way, an effect the artist has described as akin to standing in a quiet hallway outside a crowded room. Mirza’s use of auditory phenomena in conversation with space draws our attention to something we tend to encounter and perceive unconsciously—how architecture defines sound, which in turn affects our understanding of space. Unseen movements, vibrations, and waves of noise impact much of how we understand the world around us. (This is obvious when we think of the science and engineering that goes into constructing auditory spaces—theaters, churches, recording studios, concert halls—but it is less apparent in our daily lives.) In addressing architecture in this way, Mirza highlights and shifts our modes of perception, giving a physical and visual dimension to sound while creating an overt sensation of space.

This interplay between sensory perceptions and the desire to reorient our ways of experiencing the world is critical to Mirza’s work and it extends to the predicament of how to represent a sound-based work of art. Like most artworks, an auditory artwork primarily circulates in the world as a digital image—a picture depicting the work’s physical components or the space in which it was set. This presents a paradox for experiential artwork of any kind, an implicit request for viewers to extend their imaginations to give life to an action or sound that cannot be seen. Mirza often plays with this synesthetic contradiction of “seeing sound,” creating complex installations that link sound and visual phenomena as well as exploit the aesthetics of the production of sound and music (employing audio devices, electronics, musical instruments, and soundproofing materials, among others).

While Mirza is sensitive to the concerns of visual art and imagery, it is a precision of materials and forms and a lack of decoration that define his works. Each component, while aesthetically considered, has a critical role to play in the mechanics and experience of a piece. Simple things—commercial speakers, electrical cords, LEDs, and industrial foam—are orchestrated into a singularly considered installation, employed for their functionality, but transfigured into something that ultimately resists any notion of usefulness. And while precision might suggest a real-world logic, Mirza’s works have an illogical, interventionist impulse about them. They are above all experimental: physical manifestations of propositions, ideas, and questions that emerge around sound, objects, and space.

Mirza has described himself as interested in “discovery”—not in massive shifts, but rather in “tiddly-wink,” or minor, changes.3 In revisiting the recurrent physical structure that makes up this project—a circle of speakers in an anechoic space—Mirza opens up the possibility for these discoveries, for the minute and profound ways each site and each gesture can create a radically new experience for his audience. The immersive interplay between sound and light, between echo and silence, and between design and randomness in A C I D G E S T creates a particular and encompassing temporal structure that moves us slightly outside ourselves. Our perceptions and our sense of time become disjointed and reconfigured by the work’s pacing and its visual and auditory reconfiguration of space—we can become swept up in the experience, grounded but momentarily transcending ourselves.

Diana Nawi—Associate Curator

Biography

Haroon Mirza (b. 1977, London) received a BA from Winchester School of Art at the University of Southampton, United Kingdom, and an MA from both Goldsmiths at the University of London and Chelsea College of Arts, London. His work has been featured in exhibitions worldwide, including the Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver; Pivô, São Paulo; Nam June Paik Art Center, Seoul; Museum Tinguely, Basel; the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; Villa Savoye, Paris; the Hepworth Wakefield, United Kingdom; and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art, United Kingdom. He is the recipient of the Calder Prize, the Nam June Paik Art Center Prize, the Zurich Art Prize, and the Silver Lion of the 54th Venice Biennale.