He was a brilliant man with a beautiful, deep bass voice that captivated audiences around the world. He graduated from Columbia Law School after becoming an All-American football star at Rutgers University. Paul Robeson (b. 1898, Princeton, New Jersey; d. 1976, Philadelphia), the most successful African American singer of the 1940s, was a multifaceted individual who embodied excellence––a fully athletic, intellectual, and artistic being. Robeson was the son of Reverend William Drew Robeson, a slave from North Carolina who escaped to New Jersey through the Underground Railroad (a system of secret routes that helped slaves escape to the north), and Maria Louisa Bustill, a Quaker schoolteacher from New Jersey of American Indian, African, and Anglo-American descent. After practicing law for several years, Robeson’s strong belief in art’s capacity for social transformation led him to seek a career as a performing artist. During the McCarthy era (1947–56), a time in which thousands of Americans were investigated and accused of being Communists or Communist sympathizers, Robeson used his fame to advance activist causes, including fighting for the rights of workers and minorities. In 1946, Robeson created the organization American Crusade Against Lynching and, along with other prominent American entertainers such as Orson Welles and Frank Sinatra, asked President Truman to stop the mass lynching of blacks in the United States. The president declined. Denouncing fascism, Robeson traveled to Russia, China, and Europe as a civil rights activist. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) placed him under surveillance as early as 1937, and he was later blacklisted in 1949 when he spoke at the Paris Peace Conference about the reality of the treatment of blacks in the American South. Upon returning to the United States, his passport was revoked. Robeson was falsely labeled a Communist and his stardom was overshadowed by the government’s ongoing persecution; the majority of his planned US concerts were canceled.

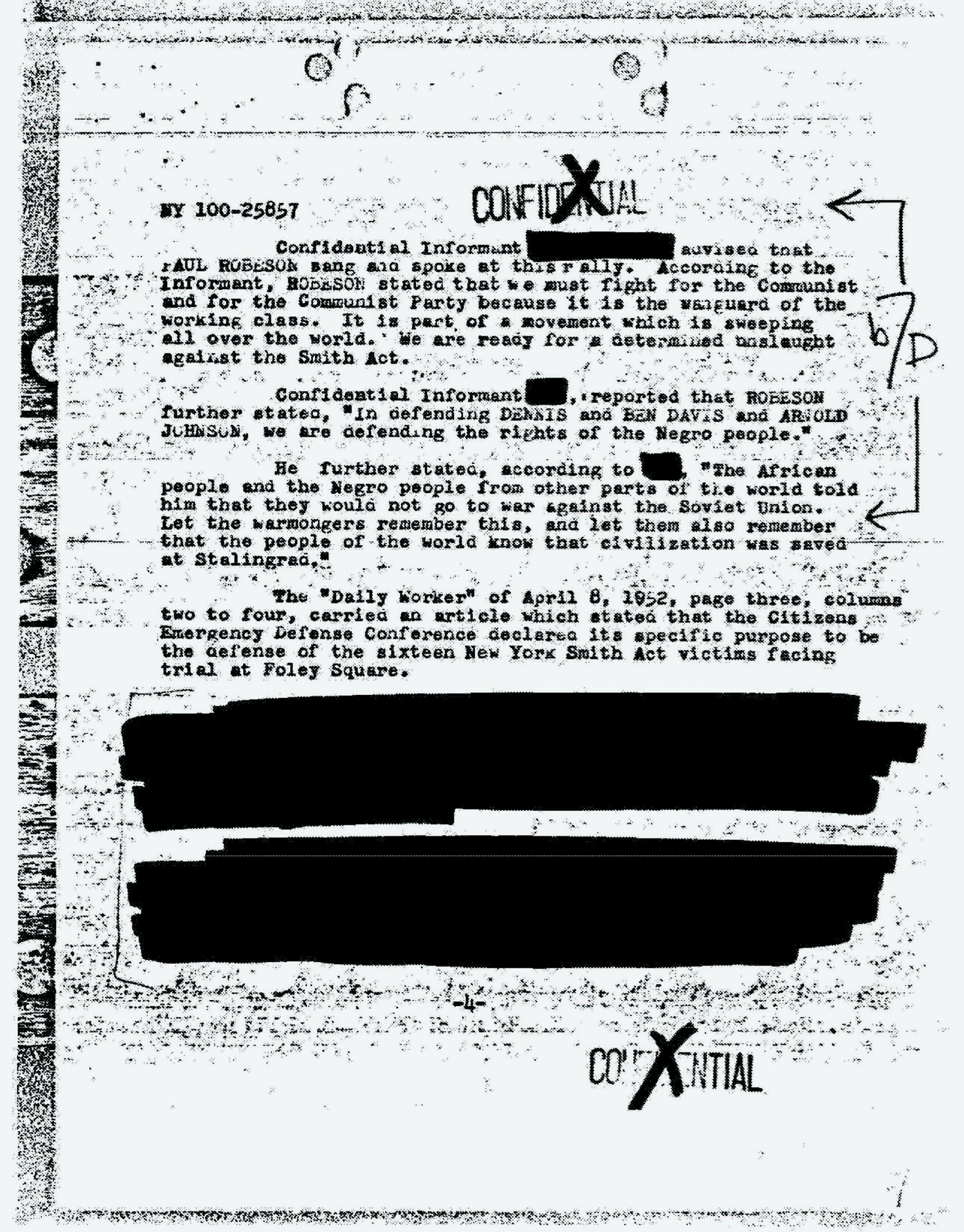

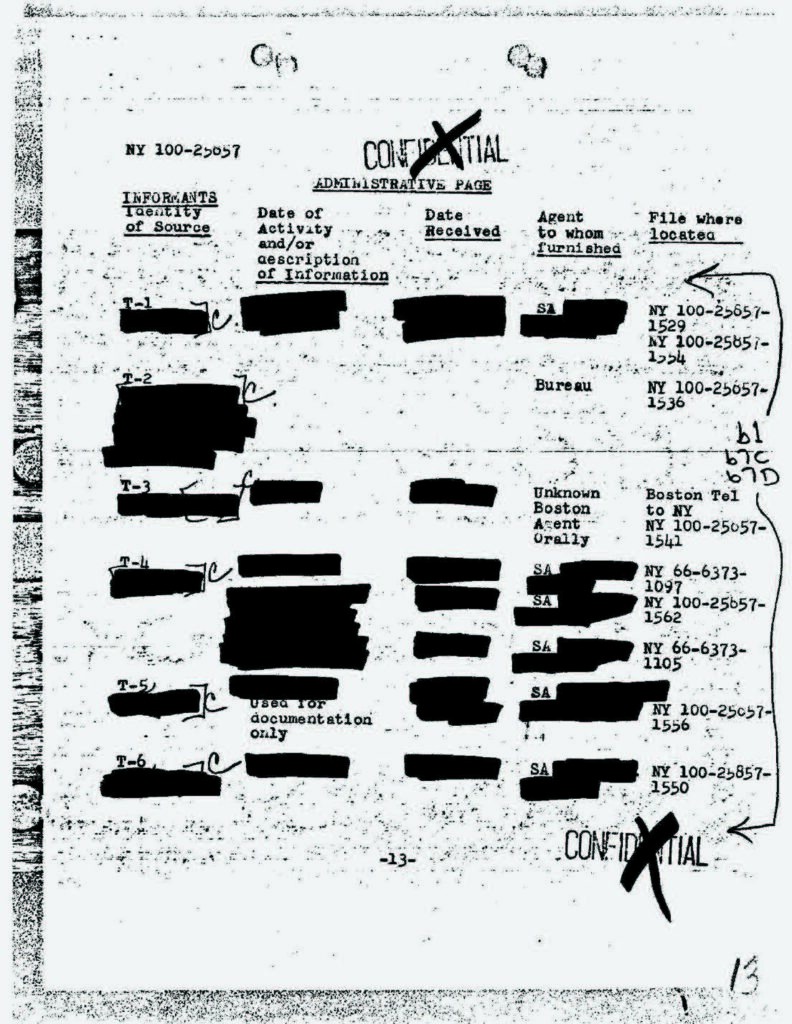

Paul Robeson is the central figure of End Credits (2012–17) by film director and video artist Steve McQueen. This immersive, durational video installation manipulates text and sound to illustrate to viewers the extensive nature of the now declassified dossier the US government compiled on the American star. McQueen received access to the files through the Freedom of Information Act, which provides any person with the right to request information and agency records from the federal government.1 He scanned every page of the government’s archive, which includes newspaper clippings, interviews, and surveillance, and turned the documents into a video sequence. McQueen then recorded male and female actors reading aloud the texts of selected pages in Robeson’s FBI record. Their voices have a cold, narrative quality. On the screen, one can barely read any of the documents’ contents, as the scrolling pages are presented at a rapid speed. Several documents have blacked-out sections that censor parts of sentences and paragraphs, including the names of FBI agents and other civil informants who aided in the gathering of information. The male and female voices read phrases used to describe Robeson, such as “negro singer Robeson,” “noted negro singer,” and “distinguished negro singer.” The files reveal Robeson’s activist and professional activities, from raising funds to fight for the betterment of Hispanics and Jews living in the United States to singing in concerts. The documents show his support for leftist organizations and events such as the Conference on Puerto Rico’s Right to Freedom, the Committee to End Jim Crow in Baseball, and the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee, among others. At one moment, the video’s voiceover details the officials’ concern when Robeson received a letter written in Chinese. Suspecting it to be a Communist communication, the FBI investigated and later disregarded it when it was discovered that the letter was from an American friend learning Chinese. There are several instances like this, in which information is gathered in fear and then discarded, but Robeson’s progressive ideologies continued to be collected with suspicion. In End Credits, McQueen highlights Robeson’s intense surveillance and harassment, capturing the rampant persecution of the left during the McCarthy era.

End Credits comprises a fragmented and abstract portrait using experimental video strategies, such as scanning documents instead of filming them. Using a scrolling effect, McQueen’s work mimics the way credits are commonly displayed at the end of a feature film. His use of sound and text embraces the immersive qualities of video, allowing viewers to become active participants in the uncovering of the materials. In this sense, one experiences the archive in real time and becomes complicit with the content at hand. McQueen’s use of duration highlights this aspect of the work, as the video lasts more than 5 hours and the audio more than 19 hours, prompting viewers to be entirely consumed by it. End Credits can be interpreted as a critique of the archive itself, which lacks significant information, including Robeson’s many accomplishments. One is left wondering: Who were the informants? What did they see that first aroused their suspicion? Who were the FBI agents? How was this information composed and manipulated? In the end, the government was never able to prove that Robeson was a Communist.

In 1958 the government returned Robeson’s passport. Although already at an advanced age by this time, he was allowed to travel and give concerts abroad. Yet the FBI’s surveillance continued until his death. End Credits exposes the political persecution of an American whose legacy as an artist and activist who embraced and elevated African American culture prevails. Like the dramatic climax at the end of a feature film–– or in this case, the end of an extraordinary life––End Credits immortalizes Robeson’s commitment to social transformation.

María Elena Ortiz—Associate Curator

Biography

Academy Award winner, Steve McQueen, OBE, CBE, (b. 1969, London) is an artist, film director, producer, screenwriter, whose work focuses on historical narratives, politics, race, and other themes concerning a deep social consciousness. His critically acclaimed film 12 Years a Slave (2013) centered on the life of Solomon Northup and received several awards including the Academy Award for Best Motion Picture. He began his formal training studying painting at Chelsea College of Arts and Goldsmiths College, London, and pursued film at the Tisch School at New York University. He has had solo exhibitions at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Espace Louis Vuitton, Tokyo; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Art Institute of Chicago; and Schaulager, Basel. His work has been included in group exhibitions at the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich; Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Philadelphia Museum of Art; Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid; and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He was also included in Documenta X and XI and the Venice Biennale in 2015, 2013, 2007 and 2003.