Introduction

In 2013 Jorge M. Pérez, together with the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, initiated the PAMM Fund for African American Art with a major grant to be used for the purchase of contemporary art by African American and African diasporic artists for the museum’s permanent collection.

In 2017, with additional generous donations from the PAMM Ambassadors for African American Art and a second matching grant from the Knight Foundation, PAMM created an endowed fund that today serves as a powerful mechanism for the diversification and enrichment of the museum’s holdings.

Polyphonic: Celebrating PAMM’s Fund for African American Art brings together the fruits of these efforts for the first time. The paintings, sculptures, and photographs on view in this exhibition have already become keystones of the museum’s collection, including outstanding works by Terry Adkins, Romare Bearden, Kevin Beasley, Ed Clark, Theresa Chromati, Leslie Hewitt, Al Loving, Lorraine O’Grady, Ebony G. Patterson, Faith Ringgold, Tschabalala Self, Vaughn Spann, Martine Syms, Juana Valdés, and Nari Ward. This broadly sweeping selection encompasses lush, expressionistic paintings and rigorous conceptual interrogations, prime historical works by established figures and exciting new entries by younger artists, politically charged statements decrying state violence against black bodies, exuberant representations of African American everyday lived experience, and works that exemplify the pursuit of pure aesthetic beauty.

The title of the exhibition points to this multiplicity of perspectives and testimonies, conjuring the idea of distinct artistic voices united in a spirit of harmony and solidarity. At the heart of this metaphor is a rejection of the premise that there is anything like a single, unified African American artistic style or tendency. In contrast to historical efforts to dictate that African American artists should conform to one mold or another, Polyphonic revels in the rich syncopation that characterizes contemporary African American artistic production, animated as it is by an intricate interplay of points and counterpoints. By giving free rein to this diversity of methodologies, we can begin to better understand the staggering scope of African American achievements in recent visual art.

PAMM has a proud 35-year history of presenting modern and contemporary art by individuals of underrepresented communities from the United States, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean. Forged amid the cultural upheavals of the 1980s and early 1990s—in which questions of race, class, gender, and ethnicity took center stage—PAMM’s mission is profoundly informed by issues of identity and intersectionality. The museum’s very first acquisition by purchase—Lorna Simpson’s Still, a monumental, wooded landscape on felt, which she created for her 1997 exhibition at PAMM’s predecessor institution, Miami Art Museum—exemplifies how these concerns have long guided both the growth of the museum’s collection and its ever-developing exhibition program. Subsequent acquisitions of important works by Sanford Biggers, María Magdalena Campos-Pons, Rashid Johnson, Wangechi Mutu, Odili Donald Odita, Henry Taylor, Kehinde Wiley, and many others have continued to add texture to this core aspect of PAMM’s institutional identity. Amid a recent upsurge of interest in works by African American artists in the international art market, this early dedication serves as an important guidepost, indicating the extent to which art by African American and African diasporic artists is hardwired into PAMM’s very DNA. Thanks to PAMM’s Fund for African American Art, the museum is now ideally positioned to extend this legacy powerfully into the future.

Terry Adkins

b. 1953, Washington, DC; d. 2014, New York.

Combining an interest in music and sound with a grounding in materiality and found objects, Terry Adkins’s works move seamlessly between the realms of performance, music, and sculpture. His multimedia performances employed unique, handmade instruments to explore different histories through sound and staging. Through both his sculptures and time-based work, he gave form to narrative and music, imbuing physical objects with the ephemeral quality of experience and sound.

Composed of the brass-colored bells of two tubas connected by woven industrial tubing, Adkins’s wall-hung sculpture Behearer exemplifies the central concerns and methodologies of his practice. The title references a 1973 jazz album by Dewey Redman and a play on the word “beholder” that substitutes sound for sight. The piece was created as part of a larger project exploring Ludwig van Beethoven’s loss of hearing as well as the possibility of the composer’s Moorish roots. Through its materials and form, Behearer evokes music even in its inert state––allowing viewers to imagine, or “hear,” the sound it would produce in their minds, much as Beethoven would have done while composing.

Romare Bearden

b. 1911, Charlotte, North Carolina; d. 1988, New York.

In 1964, Romare Bearden created 21 small collages, which he then converted into large black-and-white images using a Photostat machine, a precursor to the modern photocopier. Among the earliest artistic usages of this process, Projections, as the series is known, depicts highly emotive scenes of everyday African American life in rural and urban contexts.

Evening 9:10, 461 Lenox Avenue portrays three individuals—two men and one woman—sitting around a dining table playing cards in a cramped Harlem apartment. The image bears the quality of an intimate, first-person eye-witness account, providing a rich and highly specific visual description of mundane life. At the same time, it hums with an underlying sense of the familial and community bonds that unite its subjects.

Kevin Beasley

b. 1985, Lynchburg, Virginia; lives in New York.

Kevin Beasley combines found materials, clothing, and synthetic mixtures to create sculptures that reference Western art history and urban life. In Untitled (parade), the artist manipulated and molded different types of fabrics using a mixture of malleable resin to create a sculptural composition, invoking a sense of physical presence and movement. Portraying what resembles a group of ghostlike, faceless figures floating––or, as the title indicates, parading––the work presents a portrait of absent bodies, prompting viewers to replace the hollow spaces with imagined faces of the marginalized or underrepresented. Beasley draws inspiration from hip-hop culture—seen, for example, in his use of urban textiles and hooded garments—and the history of drapery depictions in Western painting, creating a mixture that imbues his work with a feeling of both liveliness and mournfulness.

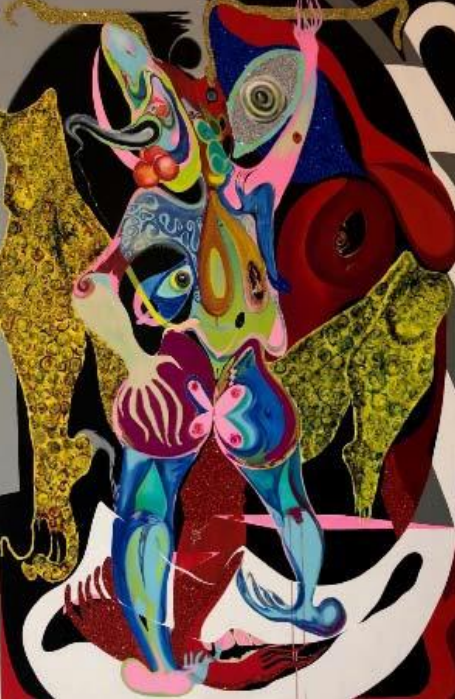

Theresa Chromati

b. 1992, Baltimore; lives in New York.

Theresa Chromati creates psychedelic, surreal paintings of black women inhabiting exuberant inner worlds. These are joyful depictions of full-figured women empowered by their bodies. The figures are adorned with bright colors and glitter and energized by brushes of paint. The women are located in fantastical environments that reference both digital and analog media. The artist creates these spaces to represent places of escape for women of color. Chromati is interested in portraying female emotions, exploring the contrast between how women present themselves to the world and their inner states of mind. She draws inspiration from Italian and French clown and pantomime traditions dating from the late 17th century––such as Pierrot––specifically how they present themselves as happy atop layers of sadness, naivete, and loneliness.

The bull is out and my foot is in my mouth (are we staying or leaving)? is a new painting Chromati made specifically for PAMM. The figure appears to be standing with her back to the viewer, her bright-pink right arm raised upward, while her left hand rests on her left buttock. The background embodies Chromati’s signature psychedelic style with bright colors and glitter, featuring incongruous elements such as eyes and bodily orifices.

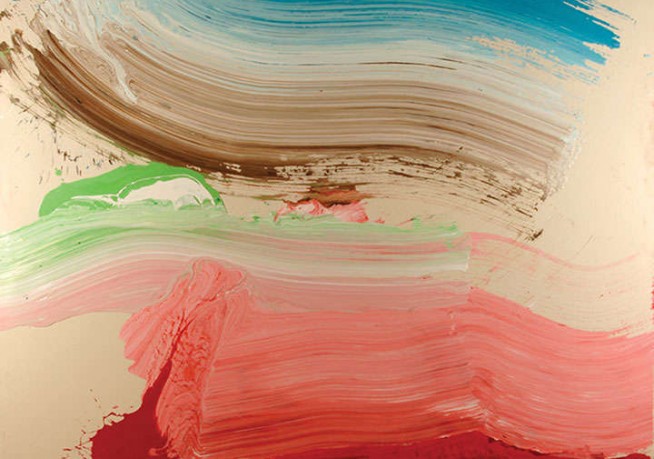

Ed Clark

b. 1926, New Orleans; d. 2019, Detroit.

After studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, Ed Clark moved to Paris in the early 1950s. The five years he lived there had a strong influence on his artistic practice. As a black artist, Clark found greater freedom from discrimination in this European city and an environment that was more open to his interests in abstraction. He returned to the United States in 1957, to New York, where he became active in the downtown art scene. He was attracted to the energy and movement conveyed in Abstract Expressionist paintings and began to experiment with different ways of placing paint on canvas.

Pink Wave represents a recent example of Clark’s technique—first developed during his early years in New York—in which he poured thick acrylic paint onto raw canvas and then moved it quickly, using a dust broom. During this process, his canvases were placed on the floor, and as a result, the paintings often contain debris picked up from his studio and embedded in the paint. Through his innovative use of the broom, Clark added a new tool to the vocabulary of Abstract Expressionism; this method allowed him to use his entire body to move the paint and gave him the ability to create broad, gestural marks. His use of the broom also introduced references to dirt, divisions of social class, and manual labor into his investigations of abstraction.

Leslie Hewitt

b. 1977, New York; lives in New York.

Leslie Hewitt’s Still Life series comprises large, framed photographs that are placed on the floor leaning against the wall. The weighty, sculptural quality that the works take on in this arrangement relate to Hewitt’s interest in the paradoxical nature of photographs as both substantive, physical objects and vessels for weightless, immaterial imagery. Untitled (Median) depicts a spare assortment of objects––a maple wood board, found snapshots, and stacked books, including James Baldwin’s seminal 1963 text The Fire Next Time. Considered a landmark in the history of literature addressing racial politics in the United States, the book interacts with the other elements in the image to convey a sense of how private, individual experience is invariably embedded within broader social contexts replete with undercurrents of political upheaval. The lemon that appears in Untitled (Median) alludes to the artist’s interest in 17th-century Dutch still-life painting; like Hewitt’s leaning photographs, this tradition often features casually strewn objects that exude intimacy while bearing veiled references to contemporaneous sociopolitical tensions.

AI Loving

b. 1935, Detroit; d. 2005, New York.

In 1968 Al Loving became the first African American artist to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Influenced by Minimalism and geometric abstraction, he exhibited paintings based on cubic forms. Shortly after this significant show, Loving became disillusioned with his own work. He later said that he “felt stuck inside that box.”

In 1972 Loving broke free of the box. He began to literally rip apart his paintings, to cut, dye, and sew together fragments of canvas, creating large, irregularly shaped wall hangings. Untitled #32 is an excellent example of his work from this dynamic period, with its strips of fabric sewn together in vertical and horizontal lines and overlaid with circular pieces that give the work a sense of movement. Loving’s mother and grandmother were both quilters and the artist recalled long hours spent watching them sew as a child, an experience that informed these pieces. The design and dyeing processes involved in his works were also influenced by West African textiles, which tie them to additional political and celebratory statements involving African traditions being pursued by black artists during the 1970s.

* Denotes works acquired with the support of PAMM’s Fund for African American Art that do not appear in the exhibition.

Lorraine O’Grady

b. 1934, Boston; lives in New York.

Over the course of more than 40 years, Lorraine O’Grady has worked across mediums to create conceptual projects that interrogate issues of identity, class, gender, and social structure. Art Is . . . was inspired by a remark made by one of O’Grady’s acquaintances that avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with black people. Struck by this statement of profound exclusion, O’Grady responded by creating an avant-garde work at one of the largest gatherings of the black community in New York—the African American Day Parade that takes place each year in Harlem. For the 1983 parade, O’Grady created a float topped with a massive gilt frame that captured everything as it passed by—turning the everyday into art. O’Grady and 15 collaborators dressed in white engaged the crowd with smaller frames, allowing parade-goers to stand in the frames and in this way become avant-garde art themselves. The documentary images taken by bystanders at the performance, collected by O’Grady and on view here, capture the joyful, spontaneous tone of this participatory work, while suggesting the sociopolitical importance of art and inclusion.

Ebony G. Patterson

b. 1981, Kingston, Jamaica; lives in Chicago and Kingston

A large figure in this work by Ebony G. Patterson is depicted kneeling at the top of the composition. Its arms are stretched back in a dramatic gesture that recalls that of surrender or emotional outcry. The piece’s tapestry structure is layered extensively with collaged fabrics, plastic jewels, lace, glitter, and beads. The dense complexity of the surface in this piece reveals Patterson’s deep painterly sensibility; she uses the diverse juxtapositions of color and texture of these found materials as a painter uses paint. Among Patterson’s chosen objects is an owl, a traditional symbol of death, covered in black glitter. A toy gun is also included, as are two shiny rubber boots filled with seashells. Shells in many African American religious traditions are believed to aid spirits in death on their journey back to Africa.

Faith Ringgold

b. 1930, New York; lives in Englewood, New Jersey

Big Black is the first in a series of works in which Faith Ringgold explores a dark palette that specifically excludes the use of white paint. Deep blues, browns, reds, and grays compose a grid filled with geometric shapes that create a face. These forms and structures are influenced by the patterns and rhythms of African sculpture, textiles, and music. Created during a period in which slogans such as “black is beautiful” were prevalent, the painting speaks to expressions of self-love. Ringgold is also influenced by the work of painters Ad Reinhardt and Josef Albers, who both created dark and nearly monochromatic abstract images. In this way, Ringgold explores the relationship between abstraction, visibility, and blackness in both their formal and social implications.

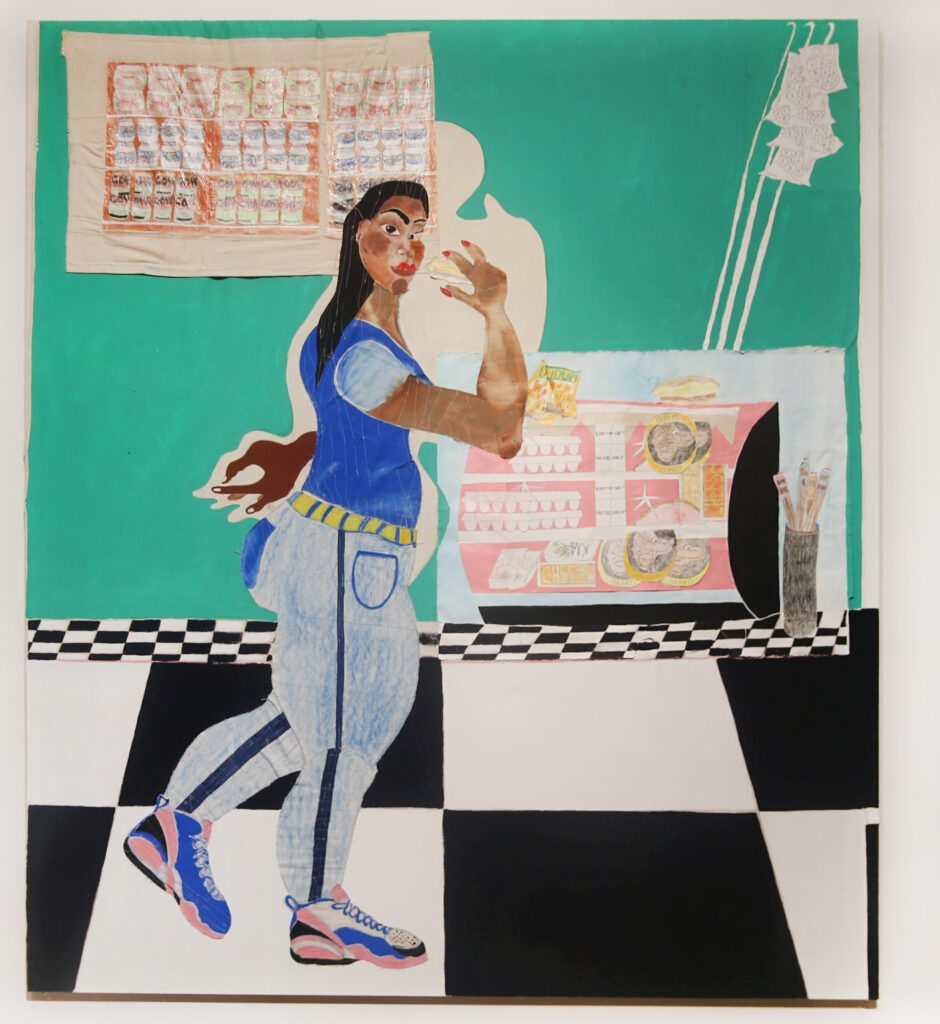

Tschabalala Self

b. 1990, New York; lives in New York and New Haven, Connecticut

Tschabalala Self’s work examines the complexities of the black body at the intersections of race and gender in paintings that combine collage with the use of textiles, paint, and printmaking. Self has recently expanded her practice to include immersive installations in works that explore the environment of the small convenience stores commonly known as bodegas in Spanish-speaking communities in New York. These installations abound with references that celebrate their social, cultural, and aesthetic significance to the primarily black and Latinx communities they serve.

Chopped Cheese comes from the installation Sour Patch, the second iteration of Self’s bodega project. It depicts a woman amid a colorful environment stocked with an array of items, eating a chopped cheese sandwich, a bodega specialty. Her trip to the store might be a part of her daily routine, indicating an everyday moment drawn from her hustle through the city. Of particular interest for Self is the agency that certain individuals are afforded in occupying public space. With this in mind, she strives to instill her characters with a dynamic sense of implied movement that suggests a breaking from social constraints. In her playful recreation of the bodega, Self-crafts a fitting environment for the character to exist freely and thrive.

Xaviera Simmons

b. 1974, New York; lives in New York

Xaviera Simmons often uses the landscape to create characters that allude to histories, memories, and fictions embedded in specific sites. Her photographs construct nonlinear narratives that present female subjects (often the artist herself) situated amid natural settings posed, costumed, and engaging in activities that reference and challenge Western notions of the “pastoral” or “sublime.”

In this work, the female protagonist is shown in a fluorescent pink dress that dramatically contrasts with the bright green leaves of the forest she inhabits. Bare-breasted, she holds a spear-like stick in her hand, lunging forward toward an aggressor, a mound of dark earth similar in shape to a large ape. Elements in the scene conjure historical and contemporary cultural references: the woman’s pose recalls images of ancient Greek or African warriors, while the ape figure evokes King Kong. Sexuality and potential violence haunt the scene. The female protagonist fights against nature, while appearing to form part of it, defending her territory.

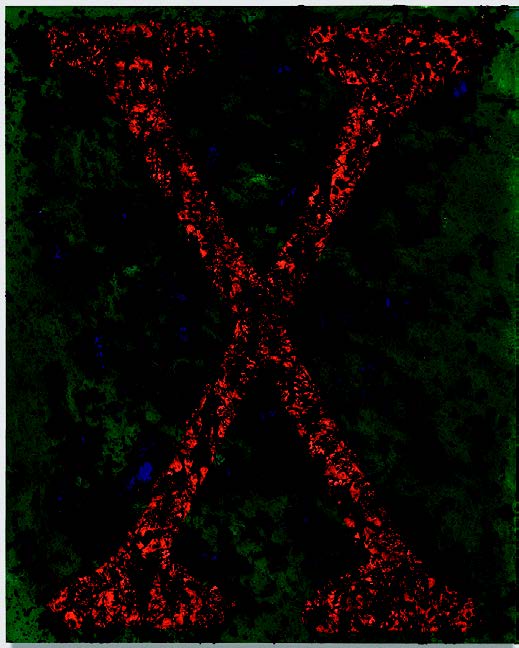

Vaughn Spann

b. 1992, Orlando, Florida; lives in Newark, New Jersey

Vaughn Spann’s paintings mine the histories of art and activism and the discourses of social practice to reflect on their inextricable relationships. His X series, for example, is inspired by his own experiences as a victim of racial profiling. “I was stopped and frisked for the first time while I was an undergrad student,” he says. “I was walking home from studying at a friend’s house. Cops pulled me over. Four other cop cars came by. They put me against a gate, and my hands are up, split. That same gesture echoes the X. And, for me, that’s such a symbolic form, and so powerful to this contemporary moment.” The highly textured surfaces of these works feature a large-scale X that fills the length of the canvas. While they vary in color, the X remains the common thread. The work’s title conjoures the identity of a specific person, suggesting a sort of portrait or perhaps a record of a particular experience.

Martine Syms

b. 1988, Los Angeles; lives in Los Angeles

Martine Syms, “The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto”, 2007–15* Paint on wall Dimensions variable Collection Pérez Art Museum Miami, museum purchase with funds provided by Jorge M. Pérez, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, and the PAMM Ambassadors for African American Art. https://www.pamm.org/es/artwork/2016.27

A self-described “conceptual entrepreneur,” Martine Syms works across various mediums, seamlessly blending video, photography, design, and experimental writing. The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto is a text piece that Syms presents in different formats, including wall installations, blog posts, and online video lectures. The work consists of a provocative theoretical critique of Afrofuturism, a literary and aesthetic tendency within late 20th- and early 21st-century popular culture that reconceptualizes the African American experience through the lens of science fiction. Typical expressions of this tendency propose incongruous links between African Americans and extraterrestrials, futuristic technology, space-age fashions, and travel to distant planets, offering such cosmic imaginings as a speculative means of liberation. Syms’s text takes the fantastical underpinnings of this genre to task for its lack of grounding in the real, earth-bound implications of the struggle for racial equality and social justice. The work asserts the need to radically rethink the future of race relations, but also warns of the perils of escapism. The Mundane Afrofuturist Manifesto is freely accessible as a video monologue on YouTube and in text form on Rhizome.org, an online platform for digital art.

Juana Valdés

b. 1963, Cabañas, Cuba; lives in Amherst, New York, and Miami

Juana Valdés combines photography and installation to investigate the history of commodities and to reconsider their connections to trade and consumerism. In An Inherent View of the World, she presents a collection of everyday objects that together embody the long, complex history of trade between the East and West, specifically the trading of Chinese porcelain that began in the 16th century. In this work, she includes china and other domestic porcelain wares once imported from Asian countries to be used in homes in the United States. She collected these objects from thrift stores and estate sales throughout the country, particularly in Florida. By placing the objects on a high table, Valdés reconfigures what would otherwise be a conventional display for these domestic wares. Alluding to the Western tradition of still-life painting, she offers an alternative perspective, reinterpreting the objects’ domestic quality as artifacts in the museum context, while highlighting the relationship between mass production in Asia and consumerism in the West.

The photograph A Single Drawn Line features a small reproduction of the compositions created in An Inherent View of the World. In this photograph, a wooden object can be seen among the china and porcelain. This addition may point to the United States’ role as one of the biggest wood exporters in the world, drawing a parallel between the histories of wood and porcelain in global trade.

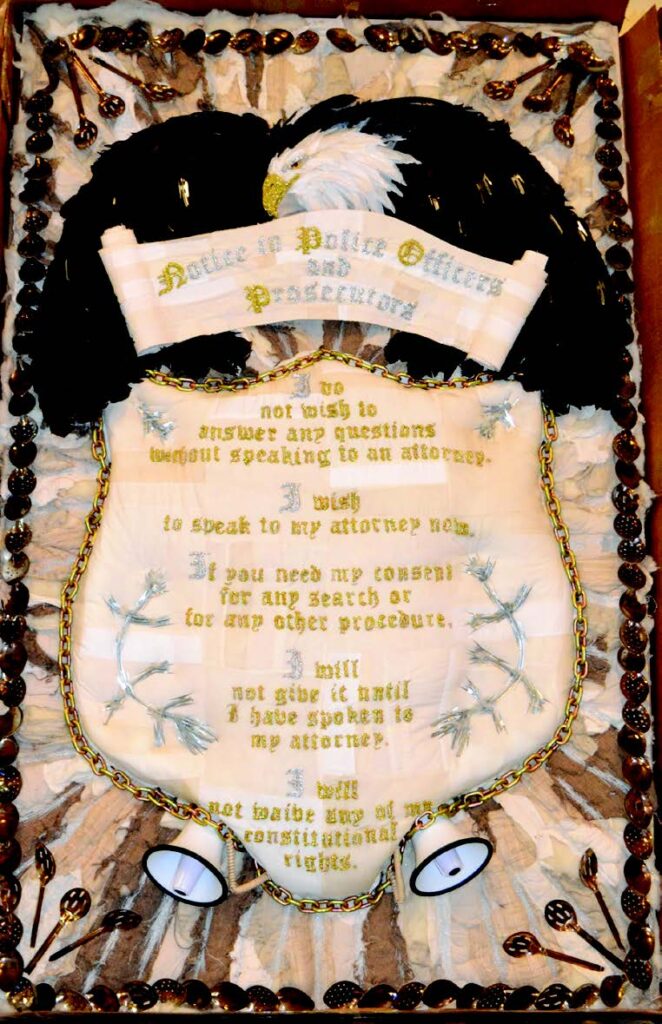

Nari Ward

b. 1963, Saint Andrew Parish, Jamaica; lives in New York.

The “Miranda rights,” a set of statements that detail one’s claims to an attorney, the right to avoid self-incrimination (the right to remain silent), and other protections, has appeared on the back of Nari Ward’s business card since 1999. He has returned to these rights in numerous works, most notably in Homeland Sweet Homeland. Ward produced this piece while in residence at the Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia, the birthplace of the US Constitution, which guarantees these civil liberties in its the Fifth Amendment. Created from an array of materials, ranging from razor wire and megaphones to gold thread and feathers, this work simultaneously suggests the form of a kitsch domestic memento and the regal scale and heraldic formality of an official government edict.