Miami, FL

72°F, broken clouds

Pérez Art Museum Miami

- 1/8 1. Introduction

- 2/8 2. Chapter One: People’s Limbo in RMB City by Cao Fei

- 3/8 3. Visual description: People’s Limbo in RMB City

- 4/8 4. Chapter Two: Reality or Not by Cécile B. Evans

- 5/8 5. Visual description: Reality or Not

- 6/8 6. Chapter Three: The Miracle of Helvetia by Guerreiro do Divino Amor

- 7/8 7. Visual description: The Miracle of Helvetia

- 8/8 8. Feedback

guide

Worlds Apart

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Introduction

The exhibition Worlds Apart presents video works by three artists: Cao Fei, Cécile B. Evans, and Guerreiro do Divino Amor. Each artist’s work creates a world where digital, physical, and imaginary realms converge. By exploring these different realities, viewers can think about how artificial worlds—whether digital or cultural—affect our sense of self, our surroundings, and social dynamics.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Chapter One: People’s Limbo in RMB City by Cao Fei

RMB City is a virtual world created by artist Cao Fei in Second Life—an online platform unlike traditional games, where users could freely build, explore, and create through digital avatars. The platform even had its own exchangeable currency and was used for education, business, and art. Launched in 2008 and open to the public in 2009, RMB City merges Chinese landmarks with surreal elements to explore how cities and society transform. The city was named after the Chinese currency, renminbi, and was inspired by Guangzhou’s rapid development, Cao Fei creates a world where Marxist symbols meet modern architecture, reflecting the changes of 21st-century China.

“People’s Limbo,” organized in 2009 as a response to the global economic crisis, became RMB City’s defining event. The event included competitions and meditative scenarios that reflected the influence of past economic realities, such as a massage parlor where historical avatars offered services while sharing their philosophical perspectives: Karl Marx, the German philosopher whose communist theories reshaped the 20th century; Mao Zedong, leader of the Chinese Communist Revolution and founder of the People’s Republic; a Lehman Brothers executive representing the global financial services firm whose 2008 bankruptcy marked one of the largest collapses in U.S. history; and Lao Tze, the ancient Chinese philosopher whose Daoist teachings emphasized harmony with nature. The event was captured in a 20-minute video titled People’s Limbo in RMB City (2009).

As her avatar China Tracy, Cao Fei transformed RMB City into a dynamic platform where visitors could explore, watch performances, and participate in events. This blurred the line between virtual and physical art, showing how digital spaces can reshape how we express ourselves, RMB City’s active participation closed in 2011.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Visual description: People’s Limbo in RMB City

People’s Limbo in RMB City (2009) is a 20-minute video featuring twelve short scenes of virtual activities documenting an event held on the gaming platform, Second Life.

The environment feels dreamlike—a fusion of real city and video game where normal rules of physics don’t apply. Tall buildings pierce neon-lit skies while objects float freely through space. Bold colors and vibrant lights create a futuristic atmosphere, with digital textures and overlapping images. Characters explore the virtual streets as playable avatars, who were controlled by artists, collectors, and Second Life celebrities invited by artist Cao Fei.

Key Landmarks

The Monument to the People’s Heroes—a granite obelisk in Tiananmen Square—bears a spinning Ferris wheel on its peak. Mao Zedong’s carved inscriptions commemorate revolutionary martyrs while water from the Three Gorges reservoir floods the square below. This vast public space, China’s political heart, has witnessed pivotal moments from the 1949 founding of the People’s Republic to the 1989 student demonstrations, surrounded by government buildings that reinforce its role as a symbol of state power.

The Oriental Pearl TV Tower, completed in 1994, rises as a giant totem symbolizing Shanghai’s transformation into a global financial hub. Beside it, the wooden Feilai Temple’s traditional Buddhist architecture creates a striking contrast. Massive concrete factories from Northeast China’s “Rust Belt,” once proud symbols of Mao’s planned economy (1950s-70s), stand as remnants of industrial history amid gleaming modern malls.

The Grand National Theatre (“The Egg,” 2007) appears to float, its controversial silver-gray surface reflecting sky and water—a pre-Olympic statement of contemporary design amid historical monuments. Planes glide over green terraces while super-malls hover alongside drifting Mao statues.

The Olympic Stadium (“Bird’s Nest”), designed by Ai Weiwei and Herzog & de Meuron for the 2008 Games, shows digital decay in its interwoven steel beams—a symbol of China’s global emergence now weathered by time.

A band performs atop a hovering Chinese flag, their music ultimately collapsing the CCTV building (2012), Rem Koolhaas’s radical architectural statement. Known locally as “The Pants,” the building’s distinctive loop-like form—created by two leaning towers bent at 90-degree angles—challenged traditional skyscraper design. Its 44-story optical illusion of instability makes its virtual collapse particularly poignant, suggesting the precarious balance between media power, architectural ambition, and institutional authority in modern China.

The fast-moving visuals, unusual designs, and dreamlike atmosphere make it feel both fascinating and unsettling at the same time.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Chapter Two: Reality or Not by Cécile B. Evans

Reality or not is a CGI video installation by artist Cécile B. Evans, presented by the School of Digital Arts (SODA) at Manchester Metropolitan University. The artwork explores how culture and reality are shaped, questioning the boundaries between what is real and what is virtual. It challenges the idea that digital and physical worlds are separate, instead suggesting that they blend in ways that are not always obvious.

Evans’s work examines how digital culture and human emotions intersect, particularly how technology influences people’s perception of reality. In past projects like Amos’ World and Sprung a Leak, Evans explored themes of individualism, collective experience, and the impact of information flow in a technology-driven society. Reality or Not builds on these ideas, continuing the artist’s investigation into how digital advancements reshape human experiences and societal norms.

The film tells the story of a group of high school students in Paris who take part in an experiment to reshape their reality. The storyline moves between different worlds instead of following a straight path. A group of teenage girls reject the roles assigned to them in a reality TV show. A statue expresses frustration with being used as a symbol. A hacker livestreams their efforts to challenge systems of power. Rather than simply depicting reality, the artwork creates a space where reality is actively produced and changed.

Evans argues that the virtual world is an essential part of daily life, influencing and reflecting reality. In an interview titled The Virtual is Real, Evans discusses the interconnectedness of virtual and real worlds, emphasizing that both continuously shape each other. Through their work, Evans invites viewers to reconsider their perceptions and understand how digital culture influences the way people experience reality.

This project was originally developed in collaboration with several international art institutions, including SODA, Fondazione MAST, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Lafayette Anticipations in Paris, Singapore Art Museum, and La Fresnoy – Studio national des arts contemporains. The artwork encourages viewers to think critically about how media, social structures, and technology shape their understanding of the world.

The mix of personal close-ups, staged environments, and confident figures suggests themes of self-expression, rebellion, and questioning what is real through the use of storytelling, technology, and speculation.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Visual description: Reality or Not

The film Reality or Not (2023) by Cécile B. Evans depicts a world where real and artificial environments blend. The work highlights how digital culture influences perception, and what people believe is real.

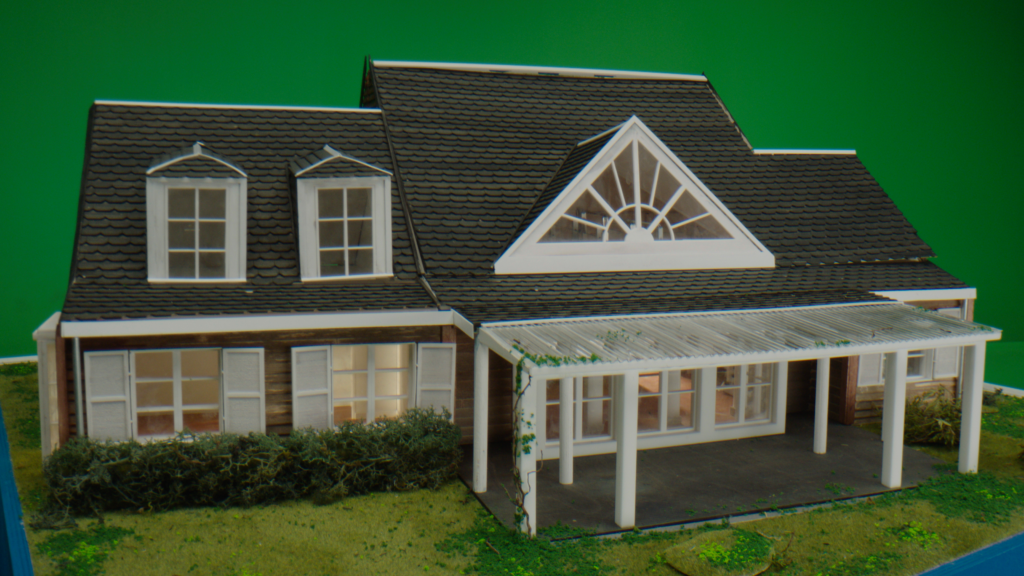

The film beings by presenting the audience with the film title Reality or Not in stylized typography, placed over a model of a house with an unusual structure. The background is a green screen, , and a small model house sitting on a white and blue structure with a brown roof and small windows. The house itself has a mix of architectural elements, with a traditional upper floor and a more modern lower section, blending styles that feel both familiar and surreal. The surrounding landscape is a grassy open space under a bright blue sky with fluffy white clouds. The setting appears idyllic but has a digitally manipulated, artificial quality,

A person, in the role of a narrator, is dressed in light-colored clothing, lies in the grass holding up a smartphone. A closer shot shows the narrator’s face looking at a phone screen, The next scene captures a close-up of a professional camera lens held by an operator. The scene cuts back to the narrator, now in the new setting of a conference room, sitting at the head of a black table, and partaking in a table reading of the film we are viewing.

The film then transitions to the narrator’s set of characters, showing a group of high school students in the northern suburbs of Paris. We then see a series of montaged scenes of the students within the film focusing on their faces in extreme close-up, showing details of skin, lips, and facial expressions. . Other camera shots show a young woman wearing sunglasses and a black outfit, standing in an indoor setting with red-framed windows and plants in the background. Her stance and attire convey confidence. A different shot features a group of young people, including a girl with blonde highlights looking directly at the camera.

These type of varied camera shots continue throughout the film: a close-up showing a hand holding a phone the group of the young students gathered in front of a mirror surrounded by bright light bulbs. . A scene showing a hand holding a pen, drawing a detailed sketch in a notebook, the student group leaning against a windowsill, looking outside with focused expressions,

These scenes take place in different spaces throughout the film; a dressing room stage area, in the cityscape of Paris, within a museum gallery, a classroom setting, and inside the virtual house the viewers are first introduced to in the film.

In parallel to the main story, the film features segments that cut away from the main storyline and introduce us to a mix of real and imaginary characters. The stories of these characters are set between the main scenes, we revisit these characters more than once throughout the film and begin to recognize the collective connections of questioned realities.

We are introduced to a butterfly that moves in secret. This bright blue butterfly acts as a secondary guide throughout the film, moving and interacting between the realities that the students are challenging. With this guide we meet a former Real Housewives star who has become a hacker and runs a secret online group.

We also meet a statue inspired by an ancient Iceni tribal leader. We meet him in a grand hall filled with white marble statues standing in symmetrical rows. In the center is our main angry statue in a long robe floating through shallow water, expressing a range of aggressive facial expressions. A large, circular stained-glass window in the background casts warm orange light and creates a dramatic contrast between light and shadow.

We also meet a group of digital characters that were rejected from their original creations and now exist in a different space. The three identical digital characters with pink hair and matching minimalist outfits stand in an assembly line, within a factory setting. Conveyor belts filled with white spheres move behind them.

Our final reveal from our butterfly character is a virtual industrial space that has been shown to us in smaller close-up frames throughout the film. A large circular machine, resembling a portal, is surrounded by metal scaffolding, control panels, and scattered equipment. Multiple blue butterflies hover around the space, appearing to come out of the center of the machine. The environment is a mix of industrial and natural elements, with moss and vegetation creeping over the mechanical structure

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Chapter Three: The Miracle of Helvetia by Guerreiro do Divino Amor

The Miracle of Helvetia is a video artwork by Guerreiro do Divino Amor that looks at how Switzerland is often imagined as a “perfect” place—wealthy, beautiful, peaceful, and balanced. At the center of the story is Helvetia, a symbol of the Swiss motherland created in the 1800s.

Helvetia has long been used as an allegorical figure, meaning she is not a real person but a character who stands in for a bigger idea. Her name comes from the Helvetii, an ancient Celtic tribe that once lived in the region that became Switzerland. During the 19th century, artists and leaders revived Helvetia as a unifying symbol for the new Swiss nation. She was often shown on coins, stamps, monuments, and government buildings, usually as a powerful woman wearing armor, carrying a shield with the Swiss cross, and standing proudly over mountains or lakes. She represented strength, independence, and the idea of Switzerland as a safe, neutral, and civilized country.

In this artwork, the artist boldly reimagines Helvetia as a monumental two-headed figure—a striking departure from traditional depictions— surrounded by a pantheon of goddesses, each representing myths connected to Switzerland, such as its wealth, political power, or natural beauty.

The video is part of the artist’s larger project, the Superfictional World Atlas, which began in 2005. This project explores how stories—whether from history, religion, politics, or the media—shape the way people think about countries and their identities. By creating “superfictions,” or exaggerated myths, the artist shows how these ideas can be powerful but also misleading.

In this chapter, Switzerland is shown as a kind of paradise where everything seems to be in balance: nature and technology, democracy and capitalism, tradition and luxury. However,But instead of celebrating this vision, the artist uses humor, collage, and surreal imagery to question it. He asks: what does it mean to create a national identity built on “perfection,” and who benefits from that story?

The work was shown as part of Superfictional Sanctuaries at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève, the artist’s first major retrospective. It was also featured in the Swiss Pavilion at the 2024 Venice Biennale, where it was presented alongside another chapter, Roma Talismano.

Through bold visuals and playful exaggeration, The Miracle of Helvetia invites viewers to think about how national identity is built—not only in Switzerland, but everywhere—and how myths of utopia can both inspire and mislead.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Visual description: The Miracle of Helvetia

The Miracle of Helvetia is a video installation created in 2022. The film opens on a cosmic stage where golden cracks spread across a dark surface. From this background, Helvetia appears as a massive two-headed bust floating above the Earth, surrounded by stars and drifting clouds. Her two heads turn together: one head has glowing red eyes that send out beams of light, while the other head has closed eyes with no other features. Below her rises a tall tower with a carousel platform holding eleven figures in different costumes. These figures are introduced as the daughters of Helvetia, each representing a different side of Switzerland.

The first daughter, Scopula, appears in a snowy scene labeled “Jungfrau – Top of Europe.” She wears white and opens her jacket to reveal a shirt covered in bright images. The images reveal, parade floats shaped like icy mountains rolling by with performers dress as safes, coins, and St. Bernard dogs with ice-skater glide across a glowing rink. The second daughter Friedena appears in white, standing near Olympic and humanitarian symbols with arms stretched out in peace. The third Gudruna wears military red, shown on decorated platforms with jets overhead and near grassy bunkers, linking her image to defense and protection.

The fourth daughter Calvina rises among brightly painted stone statues, then towers over a world map filled with ships, churches, and portraits. At a gray table marked “In Memory of Me,” she reads from a black book that reveals glowing images. Three radiant versions of her appear at once, surrounded by numbers and symbols. Ævuma, Calvina’s heiress but not one of Helvetia’s daughters, appears in a glowing green grid filled with gears, cubes, and shifting symbols. Her body mixes human and machine as she holds digital shapes with mountains, dams, and clocks layered behind her.

The fifth daughter Desideria Remotta is shown as a many-armed figure moving through palaces, dancers, cosmic skies, and DNA strands. In one scene, Switzerland’s landmass is topped with a chocolate fountain pouring into space. The sixth daughter Desideria Patria appears as a huge wooden woman crowned and standing with arms wide on a grassy hill. Around her are crowds waving flags, wheels of cheese, steaming fondue, and strange details like dragons, angels, and glowing suns. In another scene, Patria and Remotta stand together inside a giant orange sun until they merge into light.

The seventh and eighth daughters, Venuma and Silentia, walk hand in hand through a marble hall. At a glowing turquoise fountain, they dip their hands into the water. Later, Venuma appears among financial charts, while Silentia absorbs streams of data. The ninth daughter is Seminatora, wearing a red jacket, and sits behind a digital ocean filled with oil rigs and tankers. Around her are giant corporate logos—Glencore, Cargill, and Nestlé—they rise like monuments, while farms, mines, and glowing maps show the movement of global resources.

Nidustia, not a daughter, appears as a towering hybrid of skyscraper and woman, fused with Nestlé’s headquarters. She is crowned with branches and antlers, holding a fork above the mountains and waters of Alpine lakes.

The film then shifts to more realistic scenes. A helicopter lands on a rocky plateau where guards escort businessman Thomas Liechti into a high-security data center inside a mountain —a reference to Switzerland’s secretive banking and technology industries. Servers glow with the Mount10 logo, while faces of Gudruna, Venuma, Silentia, and Ævuma appear in windowpanes.

In the following scene, Silentia swings beneath the stars, her body turning into machine parts that have her body push out paper like a shredder. Venuma sits above painted clouds, sorting white powder with a straw. Below her, chaotic collages appear. They show oil rigs, roulette wheels, cathedrals, black fountains, and Calvina speaking from a balcony.

A small transitional scene follows, resembling a moment from a television series. Two women sit in a luxurious living room, speaking about education while dressed elegantly in black and white, and framed by elegant furnishings that emphasize an atmosphere of wealth, power, and refinement. This transitions us to the tenth daughter, Kulma, a deity of education who appears with blue eyeshadow and curly hair, shifting between mountain landscapes, graduation caps, classrooms, and lakeside hotels. Finally, the eleventh daughter Diewiesa Æterna rules over biotechnology, her glowing body merging with crystalline pedestals, DNA strands, and futuristic laboratories.

In the final vision, Helvetia appears once more above a starry map of Switzerland. Thirteen figures—her daughters, along with Ævuma and Nidustia—stand placed like guardians across the land. The film then concludes with sweeping Alpine views: glaciers glowing at sunrise, peaks rising above seas of clouds, and valleys hidden in mist. Across these landscapes, text appears in several languages: “I need Switzerland” (Wir brauchen Schweiz, J’ai besoin de Suisse, Abbiamo bisogno di Svizzera). These closing scenes mix mythology, tourism, and branding, showing Switzerland not only as a nation but also as a mythic entity, supported by Helvetia and her eleven daughters, each goddess embodying a distinct part of its identity.

guide

February 27, 2025 – March 1, 2026

Worlds Apart

Feedback

We hope you enjoyed this Digital Exhibition Guide!

We appreciate you taking the time to submit feedback to us as we strive to make PAMM as engaging as possible. You may submit your feedback anonymously through this form or by emailing us directly at AppFeedback@pamm.org