Miami, FL

72°F, broken clouds

Pérez Art Museum Miami

- 1/17 1. Introduction

- 2/17 2. What is Chicano/Xicanx?

- 3/17 3. Generating Pop/Sharing Vernacular: Justin Favela

- 4/17 4. Gypsy Rose Piñata (II)

- 5/17 5. Brown Commons: Yolanda López

- 6/17 6. Tableaux Vivant

- 7/17 7. Nepantla: Growth and Creativity | Celia Herrera Rodríguez

- 8/17 8. Tres hermanas: Antes-de-Colón, Colonialismo, Después-de-Colón

- 9/17 9. Nexus and Networks: ASCO

- 10/17 10. Documentation of Ascozilla/Asshole Mural

- 11/17 11. Radical Violence / Radical Resistance: Ken Gonzales-Day

- 12/17 12. Erased Lynchings #3

- 13/17 13. Disrupting Social Space: rafa esparza

- 14/17 14. Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser

- 15/17 15. Disidentify and Reimagine: Cyclona

- 16/17 16. The Liberation of CSLA! Chicano Wedding: The Wedding of Maria Theresa Conchita con Chin Gow (aka The Marriage of Maria Teresa Conchita con Chingón)

- 17/17 17. Feedback

guide

Xican-a.o.x Body

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Introduction

Xican-a.o.x. Body is the first major exhibition to feature artists who use the body to express political ideas, creativity, decolonization, and community. The title comes from “Chicano,” a term for Mexican Americans who embrace their Indigenous roots. This exhibition blends experimental art practices from the 1960s and 1970s Chicano Movement with the work of artists identifying as Mexican American, Chicana/o, Xicanx, Indigenous, Latinx, Black, Brown, and Queer.

This Digital Exhibition Guide, produced by PAMM Education, highlights and provides additional context to key artworks in this exhibition.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

What is Chicano/Xicanx?

“Chicano” is an ethnic identity for Mexican Americans who embrace their Mexican Native ancestry. According to some sources, Chicano is thought to be originally a classist and racist slur used toward low-income Mexicans that was reclaimed in the 1940s among youth who belonged to the Pachuco and Pachuca subculture. In the 1960s, “Chicano” became a term for political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in indigenous roots. It developed a unique meaning, different from “Mexican American.” Youth rejected mainstream American culture and embraced their identity as a form of empowerment and resistance. The Chicano community created a political and cultural movement, sometimes working with the Black power movement. The term is more than just a label; it encapsulates a rich, multifaceted identity that reflects the history, culture, and political struggles of Mexican Americans in the United States.

Xicanx is a modern, inclusive term that builds on the cultural and political foundations of the Chicano Movement while addressing the need for gender neutrality and intersectionality in today’s diverse community. For this digital guide, “Chicano” will be used when referring to the historic Chicano movement, and “Xicanx” will be used for all other instances.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Generating Pop/Sharing Vernacular: Justin Favela

This section looks at the way Xicanx artists contributed to the Pop art movement after World War II. These artists were influenced by the counterculture, civil rights, and Chicano movements of the 1960s and 1970s. They witnessed the Vietnam War and the student protests that followed. The younger generation of Latinx and Xicanx artists highlighted in this section continue to carry on this tradition by integrating street culture, criticizing consumer culture, and using traditional art forms for visual activism.

Justin Favela is known for creating large-scale installations and sculptures in the traditional piñata style, inspired by pop culture, art history, and his Guatemalan and Mexican-American heritage. In Gypsy Rose Piñata (II), Favela has recreated the Gypsy Rose lowrider, a 1964 Chevrolet Impala. It was one of the most famous and iconic lowriders ever made that belonged to Jesse Valadez, founder of the Imperials car club originating from East Los Angeles.

The first version of the Gypsy Rose, a 1963 Impala with 40 hand painted roses (inspired by Valadez’s mother), won many awards. It became so popular that members of a rival car club are said to have vandalized it to the point it was unsalvageable. After, the Gypsy Rose II featured around 140 hand painted roses, along with unique striping techniques, showcasing the craftsmanship and artistry of lowrider culture. It went on to gain widespread recognition through its appearance in the opening credits of the TV show Chico and the Man, which propelled it to fame and introduced the concept of lowriders to a broader audience.

Lowrider cars trace their origins back to the 1940s, when Mexican American veterans, influenced by the “hot rod” trend, began customizing their cars to distinguish themselves. Unlike the “hot and fast” hot rods, lowriders were modified to be “low and slow.” Lowrider culture has been heavily influenced by Chicano art, music, and fashion, and it serves as a form of cultural pride and resistance, particularly during the Chicano civil rights movement.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Gypsy Rose Piñata (II)

Gypsy Rose Piñata (II) is a sculpture made with found objects, cardboard, Styrofoam, paper, and glue. It measures five feet tall, seventeen and a half feet long, by six and a half feet deep.

The sculpture features a large, life-sized pink lowrider car sculpture suspended from the gallery ceiling. The car is crafted from a colorful assortment of cut tissue paper, glued together with hundreds of little squares resembling a giant piñata. The hood of the car hangs higher than the rest of the car, appearing as if it were bouncing with hydraulics. Multicolored tassels hang from its roof while layers of shiny silver ones hang from the engine. The main body of the lowrider is hot pink, with tessellated squares representing multicolored roses in the pinstripes going down its sides, roof, and trunk.

Gypsy Rose Piñata (II), 2022

Found objects, cardboard, Styrofoam, paper, and glue

Courtesy the artist and American Federation of Arts.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Brown Commons: Yolanda López

In this section, artists explore ideas of belonging and the feeling of being invisible. They question stereotypes and how race affects Xicanx people and identity, while also celebrating the natural beauty and deep presence of Xicanx life.

José Esteban Muñoz and Xicanx artists

Brown Commons adopts its name from a chapter sharing the same title in The Sense of Brown. A book written by José Esteban Muñoz, prominent Cuban American theorist who was known for his influential contributions to minority scholarship and queer of color critique. The concept of “brown commons” refers to the collective experiences, feelings, and existence of brown people. It includes various aspects of their lived experiences such as places, sounds, feelings, and objects, including both human and non-human elements. It also highlights the ways in which they are rendered brown due to factors such as migration patterns, language, contested borders, and vulnerability to systemic challenges.

Muñoz’s influence on Xicanx artists stems from his groundbreaking work in queer theory, performance studies, and critical race studies, which provided a platform for the exploration of complex and intersectional identities. His writings have had a profound impact, influencing their approach to cultural expression, identity, and resistance.

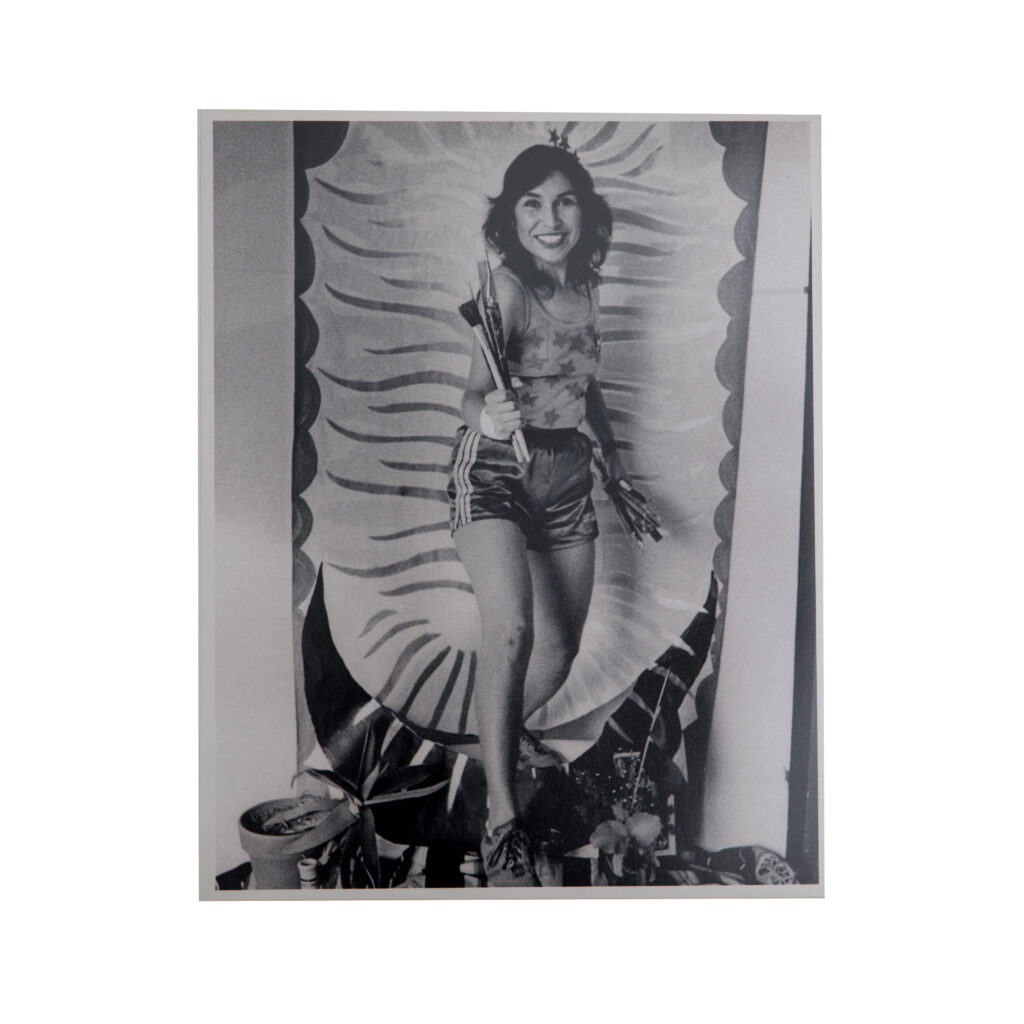

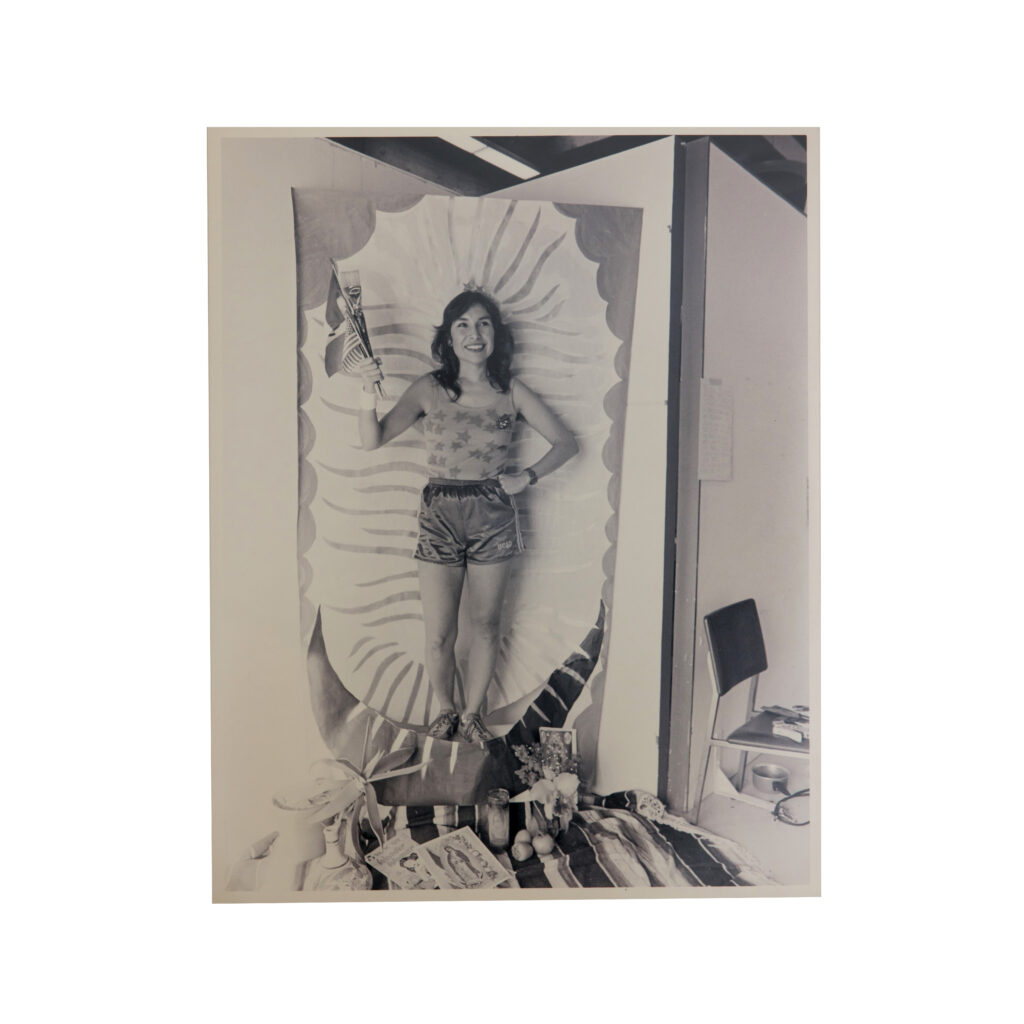

Yolanda López was born in San Diego and became one of the most important Xicana artists and activists of her generation. She attended San Francisco State University, where she became involved in student activism. Lopez’s art often addressed racial and gender stereotypes, using personal and community narratives. She was also a founding member of Los Siete de la Raza, a Black Panther-backed movement that galvanized San Francisco’s Latinx community and produced works of protest art. López’s most famous work, Portrait of the Artist as the Virgin of Guadalupe (1978), reimagines the Virgin of Guadalupe as a strong, young woman, challenging traditional depictions of women. Similarly, the photographs in Tableux Vivant (made around the same time) center on her body, elevating her role as artist to that of religious icon.

Tableaux Vivant, 1978, printed circa 1980s

Black and white photograph

Photography by Susan Mogul. Courtesy Rio Yañez and

American Federation of Arts

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Tableaux Vivant

Yolanda López’s Tableux Vivant is a series of four black and white photographs that measure approximately two feet tall by one and half feet wide. They are in portrait orientation, meaning their shortest side runs parallel to the ground.

This series of photographs features the artist, garbed in runner’s shorts and a tank top covered in stars, posing barefoot in her studio in front of a painted backdrop. The backdrop is painted with a series of wavy lines that emanate outward from her body—like a halo inspired by painted depictions of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The artist assumes several poses, with hands full of paintbrushes, her right arm raised triumphantly towards the viewer in one photo. In another photo, she smiles while holding a paintbrush coupled with both the Mexican and United States flags. Surrounding her feet, are an assemblage of artistic tools and paraphernalia—on a traditional Mexican textile are a painted vase, fruit, pictures of the Virgin of Guadelupe, a religious candle, a Mexican flag, and a potted agave.

Tableaux Vivant, 1978, printed circa 1980s

Black and white photograph

Photography by Susan Mogul. Courtesy Rio Yañez and

American Federation of Arts

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Nepantla: Growth and Creativity | Celia Herrera Rodríguez

Nepantla is a concept from the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs, meaning “in-between space” or “middle ground.” Gloria E. Anzaldúa, queer Xicana poet, writer, and feminist theorist explored Nepantla in her book Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. She used it to describe people living between different worlds, both geographically and socially, due to various forms of oppression and exclusion. Anzaldúa saw this in-between space as a place of resistance and empowerment. The artworks in this section use Nepantla’s transformative potential by embracing differences as sources of growth and creativity.

In 1994, Celia Herrera Rodríguez created a performative work and installation called Altar de las Tres Hermanas. She posed for three photographs—Las Tres Hermanas: Antes-de-Colón (Before-Columbus), Colonialismo (Colonialism), and Después-de-Colón (After-Columbus) —which were shown in gilded frames above a table with tinned Mexican and Latino foods, flanked by devotional candles with Christian virgins. The photographs contrast her devotional pose with the diminished reality symbolized by the tinned foods in the original installation, highlighting the effects of colonialism. The title Las Tres Hermanas refers to an indigenous agricultural trio: corn, beans, and squash. These plants are traditionally grown together in many Native American cultures because they support each other’s growth. This agricultural practice symbolizes harmony, sustenance, and interdependence.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Tres hermanas: Antes-de-Colón, Colonialismo, Después-de-Colón

Tres hermanas: Antes-de-Colón, Colonialismo, Después-de-Colón by Celia Herrera Rodríguez are a photographic tryptic that formed part of a larger installation titled Altar de las Tres hermanas. The photographs are almost identical in size, at about twenty inches tall by sixteen inches wide. They are in portrait orientation, meaning that their shortest side runs parallel to the ground.

For this exhibition, these three photos are displayed in their gold gilded frames without their original altar installation. From left to right, the photos are shown in the following order: Antes-de-Colón (Before-Columbus), Colonialismo (Colonialism), and Después-de-Colón (After Columbus). The three photographs show the artist in various poses dressed in white against a white background.

In the first photo, we see the artist in profile, posed in a crouched over position on her knees. Her left arm is braced around her lower abdomen, as if holding herself to comfort stomach pain. Celia’s right hand has a pinched grasp on the end of her hair, holding it up and diagonal toward the left of the photo’s frame. Celia’s face is pointed down towards the floor, and her tongue is out, giving the viewer the impression that this person is sick and is in the process of throwing up.

In the second photo, the artist is kneeling in the center, facing the viewer with her head bowed forward. Her hair is loose and relaxed upon her shoulders, and her hands are pressed together in prayer. The artist is dressed in an all-white house dress which seems to be drawn with black ink on the background rather than worn by the artist. At the bottom center of the photo is another much smaller cropped image of the artist. This smaller image shows the artist naked, posed in a forward-facing crouched position, hands placed on her knees. The placement of these two images in the photo gives the appearance that the larger figure is praying over the smaller image.

In the third photo, the artist is kneeling facing towards the right. She is looking down as her hands work with a molcajete, or a mortar and pestle tool used in indigenous Mexican culture. This tool is a stone rock bowl held on top of three stone legs, all attached as one solid stone piece. This bowl comes with another rounded stone to allow the user to place food, or medicine items in the bowl and crush them down to paste or powder.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Nexus and Networks: ASCO

The artworks in Nexus and Networks show the unity and sense of belonging in communities that celebrate their differences outside of mainstream values. ASCO was an art collective from East Los Angeles, active between 1972 and 1987. The core group, made up of Harry Gamboa, Jr., “Gronk” Nicandro, Willie Herrón, and Patssi Valdez, was created in response to the political and social issues of the time. The name “ASCO,” which means “nausea” or “repulsion” in Spanish, was chosen to show their disgust with the Vietnam War and its effects on their community, as well as the negative social and physical changes in East Los Angeles, like freeway construction that split neighborhoods and displaced communities.

ASCO focused on how politics and economic conditions in the U.S. impacted the Chicano community. They aimed to challenge the negative ways Chicanos were shown in the media with their own creative work. Through short-lived performances, films they called “No Movies,” and photos, they criticized conservative traditions and used scenes from everyday life to bring attention to violence and political issues affecting their community. In addition to the core members, the following notable artists were also involved with ASCO at one point or another, some of which also have work featured in this exhibition: Robert Beltran, Cyclona (Robert Lagorretta), Jerry Dreva, Diane Gamboa, Mundo Meza, Humberto Sandoval, and Ruben Zamora.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Documentation of Ascozilla/Asshole Mural

Documentation of Ascozilla/Asshole Mural is a framed photograph that measures approximately six by eight inches framed. The photo is in landscape orientation, meaning that its longest side runs parallel to the ground.

The image was taken by Harry Gamboa, Jr., and shows four members dressed in fashionable outfits and posing for a photo next to a large outdoor concrete drainage pipe. The large drainage hole is in the center of the photograph, with two members on each side. Patssi Valdez, is positioned on the far-left side of the pipe and is dressed in a strapless top, trousers, and white jewelry. The adjacent members, Humberto Sandoval, Willie Herrón, and Gronk are dressed in suits with their hands in their pockets.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Radical Violence / Radical Resistance: Ken Gonzales-Day

The artworks in this section resist abusive stereotypes against Brown and Black people. They confront and experiment with histories of cruelty and aim to raise awareness of trauma while highlighting humanity, resilience, resistance, and care. These works show the potential for transformation, questioning, and healing now and in the future.

Ken Gonzales-Day is a Los Angeles-based conceptual artist who explores race, identity, and representation through photography, conceptual art, installations, writing, and research. His Erased Lynchings series is based on his research uncovering over 350 lynchings of Latinos, Native Americans, Asians, and African-Americans in California from 1850 to 1935. The series uses images from lynching souvenir postcards and archival sources, where Gonzales-Day digitally removes the victims and ropes. This shifts the focus to the perpetrators and the social dynamics of the events, highlighting the historical erasure of these victims and preventing their re-victimization.

According to the NAACP, lynching postcards were a macabre form of memorabilia common in the United States from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century. These postcards featured photographs of lynched African Americans and were used to normalize and spread the ideology of white supremacy. The practice of lynching itself was a violent public act that white people used to terrorize and control Black people and people of color, often carried out by mobs with the undercover or active participation of law enforcement.

Gonzales-Day addresses historical gaps and the erasure of marginalized communities through his art. His work often emphasizes restorative justice practices, seeking to recover and publicly discuss overlooked histories and injustices. Understanding this dark chapter in American history is crucial for recognizing the ongoing struggles against racial violence and for fostering a more just society.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Erased Lynchings #3

Erased Lynchings #3 are a series of fifteen archival prints mounted on cardstock. Each framed print measures fifteen inches tall by eleven inches wide. Together, they hang in three rows of five frames each. The printed images are copies of archival documents of lynching postcards. Lynching postcards were a common form of memorabilia in the United States from the late 19th century through the mid-20th century. These postcards featured photographs of lynched African Americans and were used to normalize and spread the ideology of white supremacy. Although this series sources these violent images, Gonzales-Day digitally removes the victims and ropes. Instead, what the audience are left with are ghostly images of crowds of onlookers, trees, and empty landscapes.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Disrupting Social Space: rafa esparza

The urban landscape has played an important role in civil rights movements. Many artists in Xican–a.o.x. Body draw inspiration from the protests and marches that disrupted this social space, connecting spiritually and conceptually to these histories. Xicanx car culture, especially “cruising” in lowriders, disrupts social spaces and expresses group identity. Though banned in California in the 1980s, cruising is seen as cultural resistance, promoting socialization and community organizing.

rafa esparza’s Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser simultaneously refers to cruising on Whittier Boulevard and cruising for sex. It delves into the connections between lowrider culture, vulnerability, visibility, racial identity, labor, and technology. These archival photographs capture a sculptural performance from Art Basel Miami 2022. The piece is a futuristic cyborg lowrider bike made from a repurposed 25-cent pony ride, with parts cast from the artist esparza’s body.

During the performance, esparza becomes a human-machine hybrid, allowing select community members to ride the Terra Cruiser while listening to a whispered story of the cyborg’s mission via wireless headphones. In this story, the rider learns that Corpo RanfLA comes from a future collective, PLT/PLG (Para La Tierra / Para La Gente), aiming to heal the earth and it integrates riders into its mission to safeguard natural resources, especially corn. The cyborg’s abilities are boosted by the humans who help plant seeds for the future. Not only does esparza’s powers grow when he transforms into a lowrider cyborg bike, but the humans riding it, and their role in activating it and planting seeds, show that human effort and community is essential.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser

Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser by rafa esparsza is an installation of archival pigment prints. It contains four landscape format images thirteen by sixteen inches each, five portrait format images at nineteen by sixteen inches, and one large central image that measures four feet tall by just under five feet wide.

This artwork was originally part of a sculpture performance piece made from a 25-cent pony ride transformed to resemble a lowrider bike, with various elements substituted with casts from the artist’s own body.

The prints are arranged with the largest archival print center, which shows the full sculpture with the artist inside. The sculpture is a large bike with the artist’s body in the center, topped with a green velvet bike seat. The artist’s arms are in gold casings extending to the bike’s front gold wheel, while the upper body is visible within the frame. The lower body is in a blue and green casing, designed to resemble four legs on each side of the back wheel, all dipped in gold. The entire sculpture sits on a bright blue 25-cent pony ride machine.

On each side of the central image are nine detail photographs. Four are to the right, arranged in a tight rectangle. The top two landscape photos show the artist and sculpture with a community member in an LA performance, viewed from the right side. The bottom two portrait photos are close-ups of the bike: one of the wheel and the other of the frame with the artist inside, highlighting the tattoo on his right rib.

To the left of the central image are four photographs in a tight rectangle. The top two portrait shots show detailed views of the back of the lowrider and one of the artist’s tattoos through the bike frame. The bottom two landscape shots include a close-up of the artist’s arm in the bike sculpture and a group photo of the artist inside the sculpture with community members posing in front. The collaborators, from left to right, are Víctor Barragán, Guadalupe Rosales, Karla Ekatherine Canseco (kneeling), and Gabriela Ruiz (wearing a belt with red raffle tickets). An extra portrait photo to the far left shows a detailed image of red raffle tickets against a black background, with “Rafa Esparza” written on them. These tickets were given to guests who rode the sculpture.

Corpo RanfLA: Terra Cruiser, 2022-2023

Courtesy the artist and American Federation of Arts.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Disidentify and Reimagine: Cyclona

The artworks in this section highlight how Brown, queer people break stereotypes and defy assumptions about race, gender, and sexuality, demonstrating their diverse and complex identities. It is inspired by queer theorist José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of “disidentification.” Muñoz introduced this idea to explain how disempowered groups like LGBTQ+ and people of color deal with a world that often rejects their identity. It’s a method that doesn’t fully agree with or completely reject the main culture, a way to both question and live with the mainstream. This approach helps these groups survive and create their own unique identity and space. It shows how they can creatively challenge and change the main culture while still being a part of it, offering a deeper way to connect with their identity and the world.

Cyclona was born Robert Lagorreta in 1952 in El Paso, Texas, and moved to East Los Angeles with his family. At fourteen, he began performing on Whittier Boulevard in various costumes, often wearing women’s clothing, false breasts, and thick makeup. Often facing hostility and police harassment, these experiences taught him to provoke public reactions using his body and homemade attire, shaping his career as a performer, activist, and self-described “political art piece.”

As a student at Garfield High School during the 1968 East Los Angeles Walkouts (or the Chicano Blowouts), the civil rights struggle deeply influenced his art and advocacy for social justice. During this time, Garfield was a hub for future Chicano art leaders, like painter Mundo (Edmundo) Meza, and the founding members of Asco: Gronk, Harry Gamboa Jr., Patssi Valdez, and Willie Herrón III. In 1969, Legorreta debuted as Cyclona in Gronk’s protest performance Piglick and play Caca Roaches Have No Friends. It was then that Cyclona, inspired by a Chicana lesbian of the same name, became Legorreta’s lifelong performance persona.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

The Liberation of CSLA! Chicano Wedding: The Wedding of Maria Theresa Conchita con Chin Gow (aka The Marriage of Maria Teresa Conchita con Chingón)

The Liberation of CSLA! Chicano Wedding: The Wedding of Maria Theresa Conchita con Chin Gow (aka The Marriage of Maria Teresa Conchita con Chingón) is a collage made with printed images on fine art paper. The work is about eleven inches tall by twelve inches wide. It is in landscape orientation, meaning that its longest side runs parallel to the ground.

This collage is made on sky-blue colored paper. In the center, there are cutout white pieces of paper with blue handwriting in capital letters. The handwriting starts at the very top, embellished with small decorative flowers on either side, and reads: “CHICANO WEDDING.” Followed by, “ANNOUNCING THE MARRIAGE OF MARIA THERESA CONCHITA AND CHINGON. YOU ARE CORDIALLY INVITED TO ATTEND THE WEDDING TO BE HELD ON CAMPUS THURSDAY JUNE 3 AT NOON.”

Around the handwriting, there are three small cutout images of Cyclona wearing a long white wedding dress that drags on the ground and a white veil, while he looks up towards the sky. This work stems from the performance of the same name that took place on the campus of California State University in Los Angeles in 1971. Wearing a wedding dress and a beard, Cyclona performed an act meant to claim legal rights for gay marriage.

guide

June 13, 2024 – March 30, 2025

Xican-a.o.x Body

Feedback

We hope you enjoyed this Digital Exhibition Guide!

We appreciate you taking the time to submit feedback to us as we strive to make PAMM as engaging as possible. You may submit your feedback anonymously through this form or by emailing us directly at AppFeedback@pamm.org

Related Content

In Conversation with Priscilla Alejandre by Armando Zamora

Xican-a.o.x. Body