Miami, FL

50°F, scattered clouds

Pérez Art Museum Miami

- 1/16 1. Introduction

- 2/16 2. Carmen Herrera: Alba

- 3/16 3. Visual description: Alba

- 4/16 4. Glexis Novoa: Sin título (La etapa práctica)

- 5/16 5. Visual description: Sin título (La etapa práctica)

- 6/16 6. Myrlande Constant: Invocation for Saint Anthony

- 7/16 7. Visual description: Invocation for Saint Anthony

- 8/16 8. Viktor El-Saieh: Fet Chaloska

- 9/16 9. Visual description: Fet Chaloska

- 10/16 10. Lorna Simpson: Night Light

- 11/16 11. Visual description: Night Light

- 12/16 12. Bony Ramirez – Fiera: Views from the Outside

- 13/16 13. Visual description – Fiera: Views from the Outside

- 14/16 14. Chris Ofili: Iscariot Blues

- 15/16 15. Visual description: Iscariot Blues

- 16/16 16. Feedback

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Introduction

This Digital Guide highlights a selection of works from PAMM’s Permanent Collection created by some of the most remarkable contemporary artists from the Caribbean and its diaspora. Spanning the last four decades, these artists explore themes such as language, race, migration, and Afro-Caribbean spiritual traditions from a contemporary perspective.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Carmen Herrera: Alba

Carmen Herrera is a pioneer of hard-edge geometric abstraction and a key figure within the history of Cuban concretism. For over seven decades, Herrera has forged a distinctive style drawing on the influence of Latin American Concrete Art, European Constructivism, as well as Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism and the Abstraction-Création movement in Paris. Her pictorial investigations on abstract art prefigure those of Op art and Minimalism, with which her work is often associated.

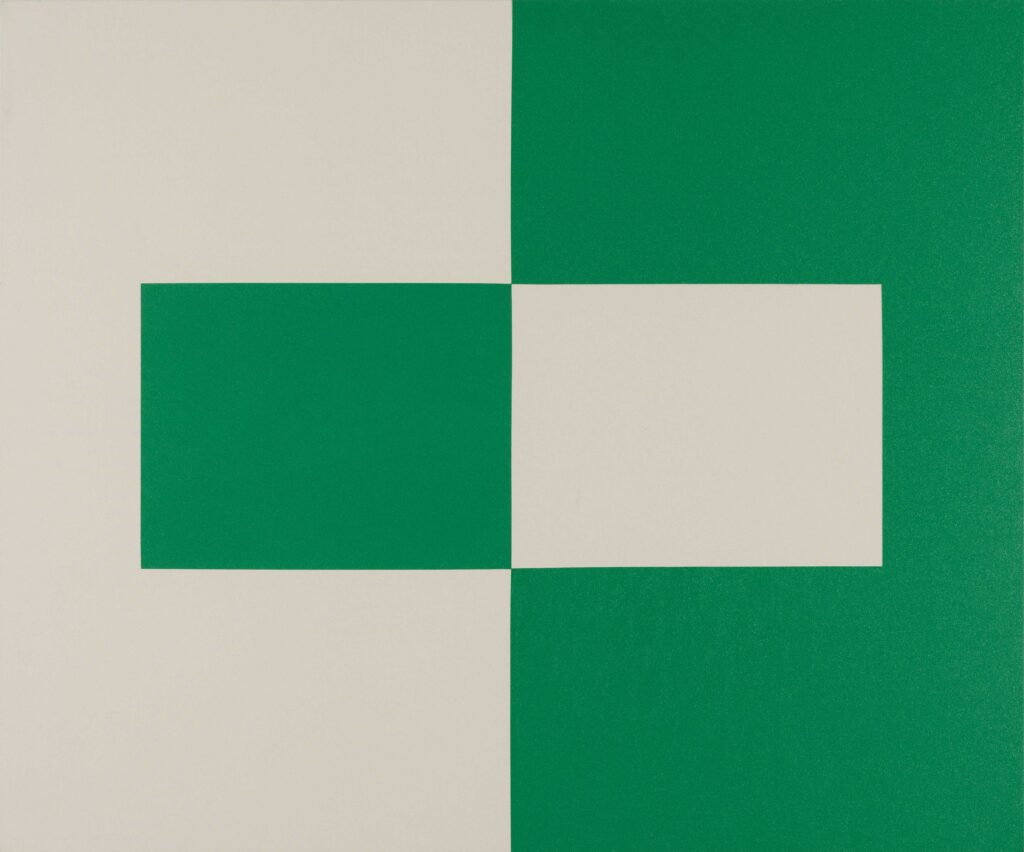

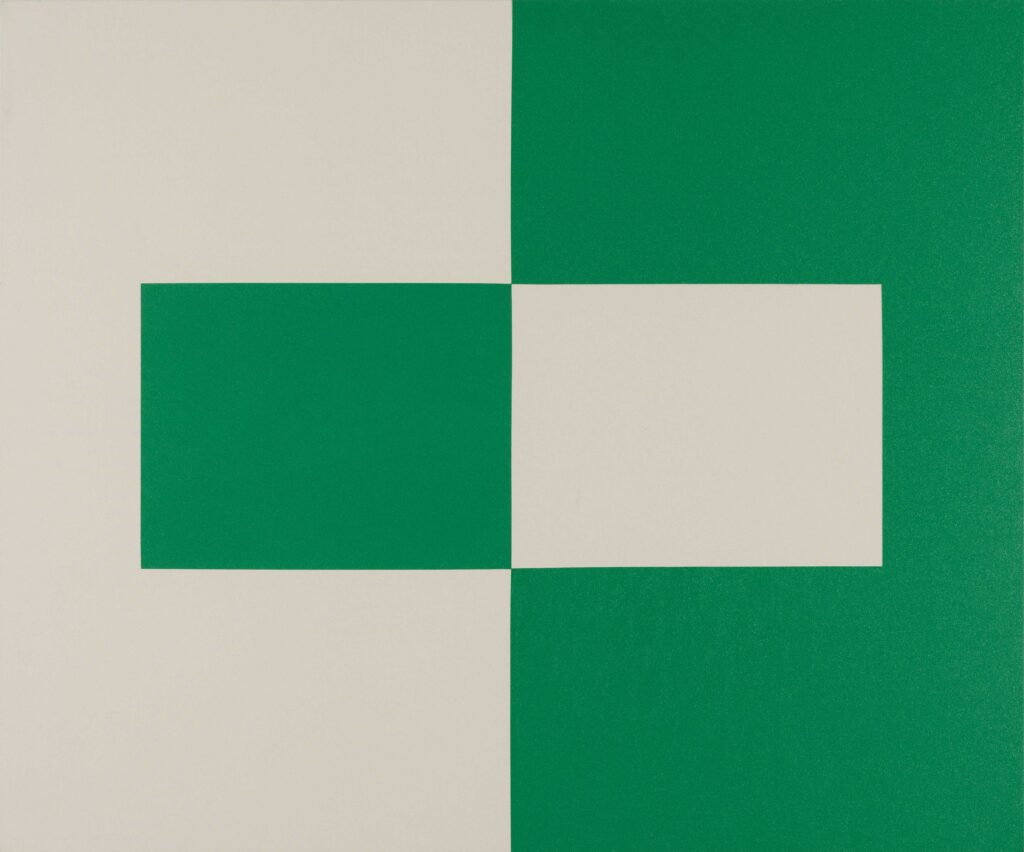

Herrera’s visual language is characterized by flat planes of color counterposed in sharp, simple, and sophisticated geometric compositions. In the painting Alba, Herrera plays with the harmony and tension created by positive/negative angular planes that alternate and balance one another, producing a vibrating sensation. In contrast to previous series where she employs two or three vivid colors in each painting, here Herrera juxtaposes bright green acrylic paint with the off-white of raw canvas. By integrating the bare material as color, Herrera adds surface texture to the composition. This strategy, which characterizes much of the artist’s work today, attests to Herrera’s constant search for innovative pictorial solutions and illustrates her interest in rendering compositions that are reduced to their very essence.

While most of Herrera’s paintings are devoid of referential elements, at times her work hints at anecdotal content deriving from the artist’s personal experiences. In this sense, Herrera’s Alba could be read as a subtle reference to Alba-la-Romaine, a Roman village in the French countryside where Herrera spent several summers while living in Paris in the early 1950s. Alba’s angular shapes can be considered as a simplified rendition of the historic Alba castle or the Roman fortress that surrounded the ancient town; while the off-white color and texture of the raw canvas could be associated with the old houses made from carved stone where Herrera, and many other international artists, lived or used as art studios.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Alba

Alba, by Cuban born artist Carmen Herrera, is an acrylic painting on canvas. It measures sixty inches, or five feet, by seventy-two inches, or six feet. Alba has a landscape orientation, meaning the side that measures six feet, its longer edge, is parallel to the floor when seen hanging on a gallery wall.

This painting is an example of geometric abstraction, in its truest sense, because of its bare and simplified shapes, sharp ninety-degree angles, and lack of any visual representation. The entire artwork is organized around a vertical line of symmetry that starts in the middle of the top edge of the canvas. This line perfectly divides the canvas down the middle, separating it into left and right halves. On the viewer’s left, this portion of Alba is unpainted, exposing the neutral off-white color of untreated canvas. The bare canvas extends to the top, left, and bottom edges of the frame. This blank canvas ends abruptly at the central line of division. From this line moving right, the other half of the rectangular canvas is painted entirely in a saturated green hue, establishing a sharply divided off-white on the left and green on the right rectangular artwork.

In the center of this painting is a smaller rectangle, that inverts the established color scheme of the larger canvas. This central rectangle is green on the left and unpainted on the right.

The smaller rectangle comes short of stretching to the extreme left and right edges of the canvas. On either side, there is a strip around six inches wide of the underlying, opposite color. In a way, it looks like the green and beige halves of Alba overlap upon one another. They look as though they are both occupying, and being occupied, by the other.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

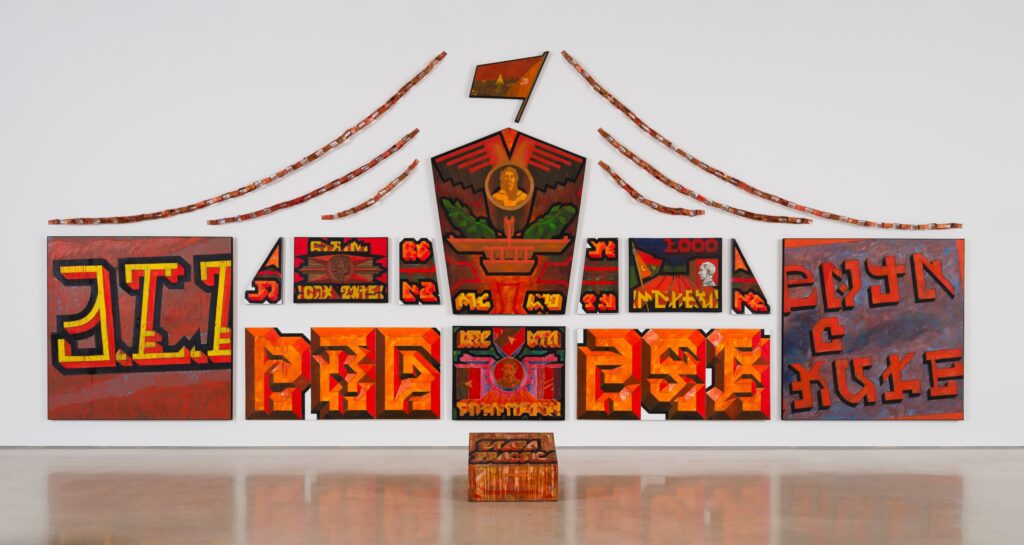

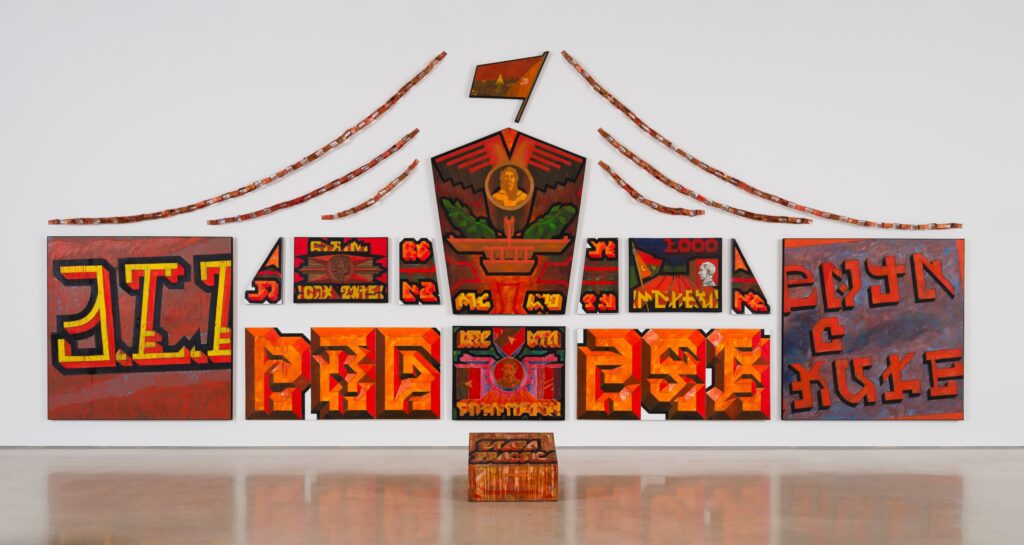

Glexis Novoa: Sin título (La etapa práctica)

Treading a delicate line between the political and the absurd, Glexis Novoa’s Sin título (La etapa práctica) is a multi-panel installation inspired by the style and visual elements of propaganda art promoted by totalitarian regimes. This aesthetic is manifest not only in the monumentality of the piece, which evokes the pomposity of Soviet Socialist Realism, but also in the predominance of red and yellow. Moreover, the artist has incorporated characters resembling letters of the Cyrillic alphabet (the official Russian alphabet). Though the script in the panel to the far right appears indecipherable, upon closer inspection, it may recall the iconic slogan of the Cuban revolution, “Patria o Muerte” (Homeland or Death). Meanwhile, the letterforms in the panel on the far left bring to mind the initials “PCC,” which stand for “Partido Comunista de Cuba” (Communist Party of Cuba), Cuba’s ruling party. The work also includes portrait roundels that though unrecognizable were inspired by iconic political or cultural figures, such as Che Guevara and the revolutionary singer Silvio Rodriguez.

In Cuba, where the use of national symbols like the flag or the country’s coat of arms is outlawed outside of official political contexts, Novoa was able to escape censorship through subtle mockery and a deft use of abstract symbolism. Alluding to the title of the work, a commemorative plaque resembling a podium extends three-dimensionally from the center of the wall installation, further highlighting the empty political rhetoric and lack of freedom in contemporary Cuba.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Sin título (La etapa práctica)

Sin título (La etapa práctica) is a multi-panel wall-based installation by the Cuban artist, Glexis Novoa. In its totality, it measures approximately thirty feet wide, with a sculptural element on the ground about eight feet in front of it that stands about two feet tall.

This mixed media installation contains several panels of assorted sizes that stretch horizontally across the gallery wall. The panels are arranged around a central, large, five-sided panel that stands above the rest with smaller panels on its sides that match each other like a mirror image. They are painted in a graphic style, with crisp lines and iconic images that resemble propaganda art. The artist also utilizes characters designed to mimic letters of the Cyrillic alphabet (the official Russian alphabet). The color palette is limited, painted mostly with rusted reds and golden yellows.

The large, five-sided (or pentagon-shaped) panel at the center of the installation mimics a political emblem. It features a rusted red circle with the yellow bust of a male who sports a beard and jaw-length wavy, dark hair, closely resembling Che Guevara. The circular emblem is topped with geometric lines that resemble bird wings, having an eerie similarity with the emblem used by the Nazi party. Above this central panel, there’s a smaller panel shaped like a waving flag painted with washed out red and black, resembling an anarchist flag with small geometric symbols across the flag’s center. Around it, three paper chains are pinned to the wall, skirting the sides of the pentagon shape and the tops of the other panels.

The installation is bookended by two large square-shaped panels that are about six feet tall. Their surfaces are almost entirely covered by the large, cryptic script designed by the artist. There are two lines of script on the panel on the far right painted in rusted red with a washy blue background. The script is slanted, with some of it appearing to continue past the edges of the panel. Upon closer inspection, the words appear to spell out “Patria o Muerte” (Homeland or Death) —an iconic slogan of the Cuban revolution adopted by Fidel Castro in 1960. Meanwhile, the bright yellow blocky letters that cover the panel on the furthest left appear to conceal the initials “PCC,” an acronym for the Communist Party of Cuba.

The sculptural element that sits on the floor in front of the wall installation is trapezoidal in shape. It is painted in muddy ochre, with rusted red paint drips running down its sides. The shape of the block resembles the top of a speaker’s podium. On its surface, Novoa has written the namesake of the work in his signature script, “etapa practica.”

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Myrlande Constant: Invocation for Saint Anthony

Invocation for Saint Anthony honors Legba, guardian of the crossroads and the first loa saluted at many Vodou ceremonies, exemplifying the strategic syncretism or blending of Catholic saints with Vodou deities that characterizes much of Myrlande Constant’s work. This richly patterned, beaded tapestry also demonstrates the artist’s mastery in the creation of drapo, or sacred flags used in Voudou rituals.

Constant learned the embroidery technique known as tambour beading as a youth, when she worked with her mother at a wedding-dress factory. As can be appreciated in Invocation for Saint Anthony, Contant’s practice is as meticulous as it is labor-intensive. She begins each composition by making a preliminary drawing on the back of a canvas stretched tightly over a horizontal wooden frame. With one hand on either side of the fabric, she works the piece from the back (which is facing up). Following the lines of the drawing, she pushes the threaded tip of the tambour hook down through the fabric with one hand, securing a bead on the other side with her other hand, and then pulls the thread back up again—in effect fixing the embellishment in place with a chain stitch. The artist works intuitively, looking at the final beaded work only when it has been completed.

Constant describes her process as “painting with beads.” By introducing new materials, techniques, and a unique style of visual storytelling, Constant has pioneered a new style of Vodou flag-making, becoming the first woman to gain international recognition for what used to be a male-dominated practice.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Invocation for Saint Anthony

Invocation for Saint Anthony is a beaded fabric by Haitian artist Myrland Constant. It is made with sequins, beads, and silk on cotton fabric. It measures forty-seven inches tall by fifty-eight inches wide, sitting at about four feet tall and just short of five feet wide.

The entire surface of the Invocation for Saint Anthony is covered in hundreds of brightly colored sequins and beads, leaving little to no trace of the cotton fabric below it. The piece was inspired by drapo, or sacred sequined flags used in Vodou rituals. It features two flat figures at its center who are surrounded by various geometric symbols within an intricately embroidered frame.

One of the figures is a Black figure who directly faces the viewer. Their brown skin is speckled with various brown beads, including some that are purple too. This figure sports a head of short white hair and a cream-colored shirt that has a pale-yellow collar and short sleeves. They sit on a black tree stump with a black cane in their right hand that is as tall as they are. The figure sits with their legs wide open, and their other hand is held just above their genitals. Below, in the space between their legs, there is an oval shape colored by upward facing chevrons in orange, white, yellow, and green. Connecting to the bottom of this oval shape is the tip of a cream-colored triangle outlined in yellow. Directly in between the figure’s legs, there is an orange beaded line. This orange line bisects the oval shape below the figure and ends at the base of the triangle below that. To the left of these shapes, sits a teal-colored bowl filled with round colorful shapes suggesting a variety of fruits and vegetables that might serve as an offering.

The second figure to the right is a white person. Their skin is made with a variety of pink and white beads. They have short gray hair on the sides of their head while remaining bald on top. This figure also holds a cane in their right hand that is wrapped in a white cloth, which is indicated by a loose piece of fabric depicted dangling from the handle. This person sits cross-legged at the foot of the black figure with their back leaning on a black tree stump to the right. The stump is covered in black, gray, blue, purple, and teal beads as if iridescent water were flowing from it. This white figure wears a bright red shirt with short sleeves. The shirt has an elaborate glossy black lapel and button placket. Their black pants have delicately embroidered sequins to match. This white figure also has a pale-yellow satchel marked with three sets of black and red arrows. From the white figure’s black eyes, a line of gray colored beads connects to the figure to their left, as if their gaze were a laser beam shooting into the other’s shoulder.

The yellow ochre-colored background behind the figures contains various multicolored vèvè symbols. In Haitian Vodou, vèvè are geometrical drawings that represent the Iwa or spirits. They can vary in complexity and are typically drawn on the earthen floor using cornmeal, dry pigment, or ashes by a Vodou priest or priestess. These symbols are central to Vodou rituals, as they are meant to direct the spiritual energy associated with a particular spirit.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

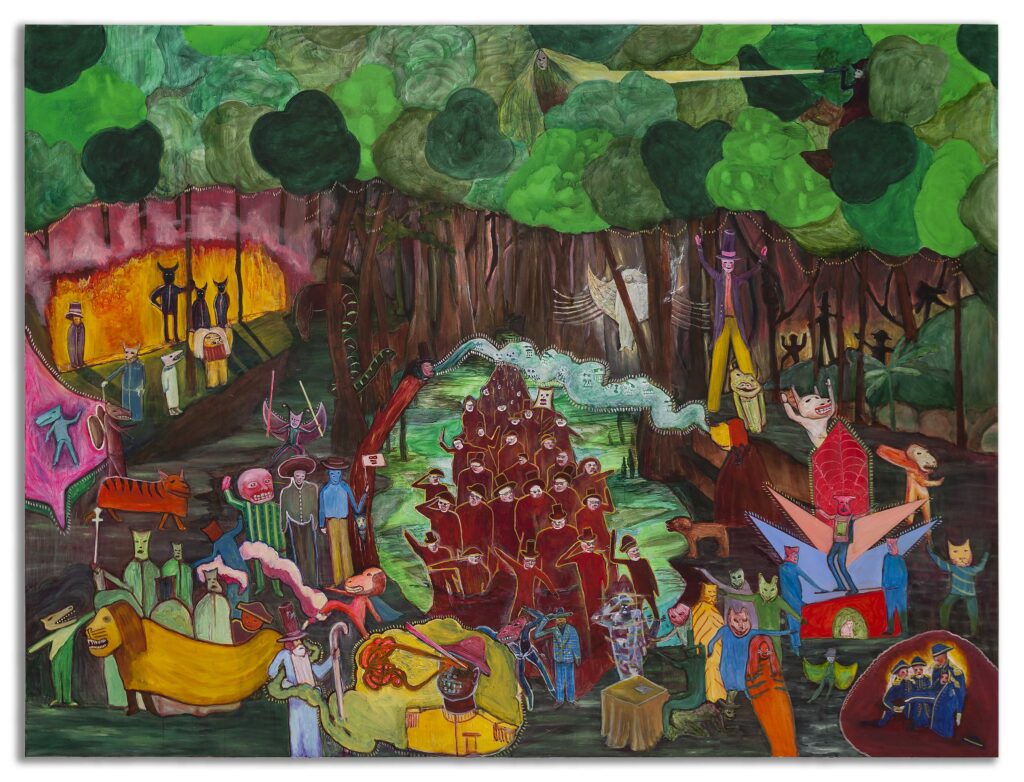

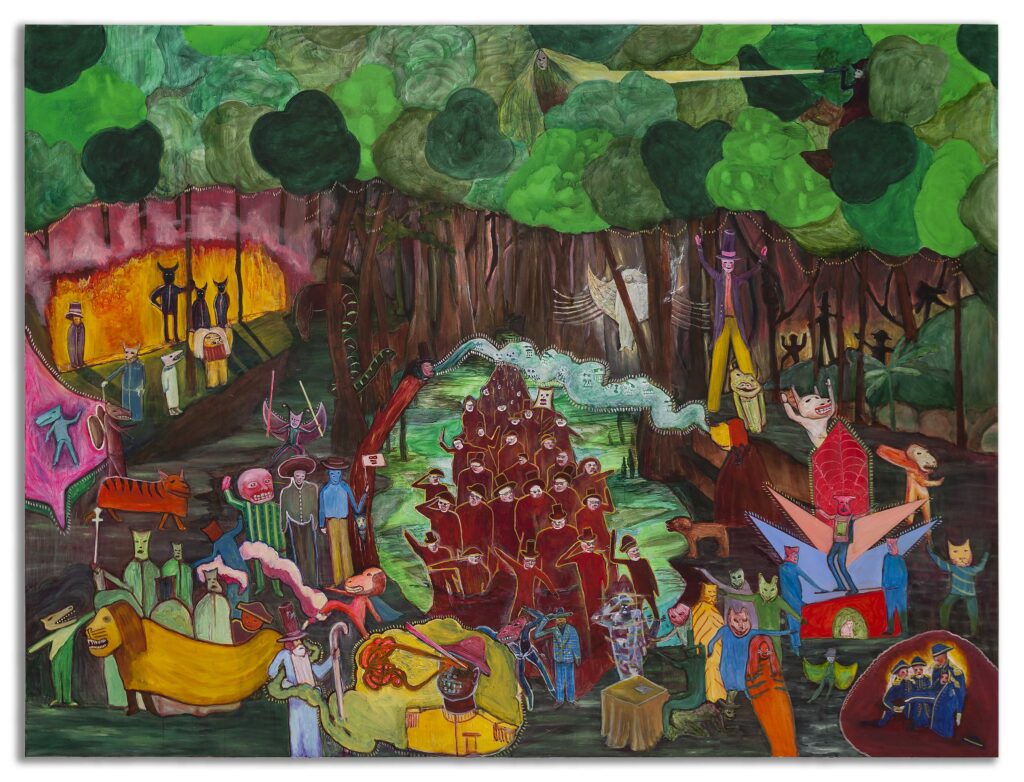

Viktor El-Saieh: Fet Chaloska

Viktor El-Saieh is a Haitian artist who’s vibrant and narrative-rich paintings examine the relationship between mythology and the complex political history of Haiti. In Fet Chaloska, or Chaloska Festival, El-Saieh depicts a surreal carnival scene set within an imaginary natural landscape populated by oversized carnival masks, stilt walkers, and colorful costumes of real and mythical animals. However, a closer look reveals a more elusive image. This painting focuses on “Chaloska,” a traditional carnival character dressed in military attire with dark sunglasses, protruding mouth and large teeth. The satirical representation of Chaloska evokes the military officer Charles Oscar Etienne, who terrorized the southern Haitian town of Jacmel and executed hundreds of political prisoners in the early 1900s.

In addition to Chaloska, this painting nods to other historical carnival characters such as the juif errant, or Wandering Jew, represented at the bottom of the scene, carrying a stick and dressed in blue robe with a long white beard. In the middle foreground, the three black figures with horns standing against a fiery background recall the grim-looking lassoers (or Lanse Kòd in Creole)—a stern reference to the history of slavery.

The repetition of Chaloska figures that appear in bright red parading at the center of the composition can be understood as an allusion to the ongoing instability and violence that has long dominated the country’s social and political landscape. At the same time, this masquerade scene can also be read as a celebration of resistance and communal creativity in contemporary Haiti. Combining the joyous and the grotesque, El-Saieh’s Fet Chaloska addresses the way in which turbulent political realities, both past and present, are transposed into contemporary Haitian culture by means of its vernacular traditions.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Fet Chaloska

Fet Chaloska, by Haitian artist Viktor El-Saieh, is an acrylic painting on canvas. It measures approximately seventy-two by ninety-six inches, or six feet by eight feet, in a landscape orientation.

This painting captures a lively and colorful carnival in a forest setting, containing various scenes across the canvas. The painting can be organized into roughly three bands, that grow progressively more animated when viewed from the top and moving downward. The top is mostly the green leaves of the trees that make up the forest setting. The middle band is mostly the tree trunks, and therefore background scenes of the carnival. The bottom band contains the foreground and main staging area of the carnival.

Starting from the top of the canvas, the top third of the painting is composed of rounded shapes in varying shades of green, indicating the canopy of a forest or jungle. On the right side of the canvas, are the first of many ghost-like figures. There is a black figure with a white face seen in profile, peeking out of the tree leaves. They are shining a flashlight on a grey face, floating among the treetops toward the centerline of the canvas.

Moving down, the middle band of the canvas is composed of the vertical trunks of the forest’s trees. In between the repeating brown columns are the first of the carnival’s many scenes. Starting on the left-hand side are various figures, three of them are black silhouettes with horns protruding from their heads. They are surrounded by orange and yellow paint, as if caught in a sectioned-off forest fire. Some of the other participants standing in their vicinity have animal heads, some of them with long snouts and bared teeth. Others have horns or whiskers. Moving toward the right along the band of tree trunks, left of the center is another ghostly image, painted in white, floating among the brown branches. The white figure has wing like protrusions coming out it’s sides and a faint face. To the left of the floating ghost, is a smiling stilt walker, standing tall and facing the viewer with his arms stretched to the sky. The stilt walker is wearing a purple stovepipe top hat that grazes the bottom of the green tree canopy, as well as yellow trousers and a purple blazer. Further to the right of the stilt walker, on the rightmost third of the canvas, are the outlines of figures seen behind the trees. They mirror the figures on the left, as they are painted in nearly all black, and with the imagery of fire behind them, however, they are located deeper within the forest.

Starting at the center of the painting, the last band fans out to the lower left and right corners of the canvas, giving the bottom third of the painting a triangular composition. This foreground at the bottom of Fet Chaloska is where the Carnival fully unfolds out toward the viewer in several different scenes. There are dozens of participants in a rainbow of colors and poses, many of them in a variety of animal costumes. Some have horns protruding from their heads, or have dog-like or cat-like masks or head coverings. At the center of the carnival, is a flood of people marching toward the viewer, like a crowded parade. These people are painted entirely in red with a thin yellow outline. They all have sunglasses and bare their teeth from outwardly puckered lips. These figures are the Chaloska, as named in the title. They are meant to be representations of a Haitian military figure from the early twentieth century. They form a triangular mass that starts as a narrow stretch of figures at the center point of the painting, that widens toward the bottom of the canvas. The figures also increase in size from the back of the parade to the front, which is located at the bottom of the painting, in order to give the illusion of depth. The Chaloska parade in a green ditch that resembles a swamp, forming a clearing between the trees and the ground. On all sides of the marching Chaloska, are other figures in assorted poses and activities, some with animal head costumes, or other face coverings. There is one man in a blue robe at the very bottom of the painting with a long white beard, tall top hat, and cane. From his mind, a green thought bubble wraps around him, and inside, is the image of a military uniform-clad man with orange and pink beams shooting out of his eyes.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Lorna Simpson: Night Light

Born to a Jamaican Cuban father and an African American mother, Lorna Simpson has explored the stereotypes associated with Black women throughout her career. In Night Light—part of her ongoing series titled Ice—Simpson presents a conceptual landscape in which her juxtaposition of the body, text, and arctic ice morph to render visible the stereotypes of Black female bodies in our society and the systematic burden placed on Black women as a consequence. In this glacial environment, Simpson creates opacities, exploring how open spaces in the gessoed fiberglass absorb layer after layer of ink to develop values of blue that suggest darkness. The top of the iceberg is sharply delineated, its shape looming behind vertical strips of undecipherable text. This form might suggest assumptions based on race that result in the stereotyping of a person. Yet, the strips unifying its top and bottom sections offer a disruption, where these same assumptions crack to reveal incomplete faces of Black women. Cut from the pages of Ebony Magazine, these breaks in the picture are but a glimpse of what lies beneath the surface, the parts ignored and not seen for the sake of oversimplifying the existence of a person. The dripping at the bottom of the canvas suggests the ever-present additive nature of stereotypes and the constant concealment of Black women as individuals.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Night Light

Night Light is a screenprint with ink on fiberglass primed with gesso. It measures approximately six feet tall by almost five feet wide. It is in vertical orientation, meaning that its shortest side runs parallel to the ground.

This work is part of Lorna Simpson’s “Ice” series, and features a snowcapped glacier covered in washes of dark blue ink. These washes of blue ink start at the top edge of the piece and drip towards the bottom, with large ink drips that make it look as if the image itself were melting. A horizon line divides the image in the middle. The water is painted in blue so dark that it’s almost black and reflects a faint image of the glacier above. There is a cloudy sky above it all. The bits of sky that peek between the fluffy clouds are also so dark with the blue ink that it looks like an oily, iridescent black night sky. This makes it hard to tell which time of day it is in the image.

There are five narrow slivers of screen-printed strips from Ebony Magazine scattered across the image. They look like glitches on a screen, cutting across areas of the work without any regard for the image below it. The strips are so narrow that it makes the text illegible. Parts of them blend in with the glacier background while others stand out in stark contrast. All but one of the strips contain small images of women’s faces placed at different heights. The faces blend in with the glacier and water behind them, making it hard to notice them at first.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Bony Ramirez – Fiera: Views from the Outside

Self-taught artist Bony Ramirez is best known for his fantastical or surreal depictions of non-gendered human figures with elongated limbs and oversize or otherwise distorted features. Combining a range of painting, collage, and drawing techniques, Ramirez’s work celebrates the artist’s Dominican heritage while exploring the complexities of Caribbean history and culture.

Fiera: Views from the Outside portrays a jaguar with a human head and rainbow-colored ears feasting on its prey in a coconut tree. The first of Ramirez’s paintings to feature a hybrid figure, one that is half human and half animal, this work marks a significant shift in the artist’s signature style. Its title—Fiera, which in English means “beast”—makes reference to Ramirez’s own experience of growing up in the United States, where he felt perceived as an outsider, savage, or beast. Drawing on magic realism, Ramirez has rendered his fiera in the body of a wild animal not native to the Caribbean islands that is devouring a species of straight-horned antelope more commonly found in Africa. Indeed, the insertion of these “foreign” animals into the tropical Caribbean landscape adds to the otherworldliness of the image.

Butterflies, many species of which are migratory, overlay the composition in a grid-like pattern. Their orderly arrangement creates a stark contrast to the ravagement occurring behind them. In this way, Fiera challenges common stereotypes of Caribbean people living in the United States while, at the same time, foregrounding the nuances and multilayered nature of the immigrant experience.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description – Fiera: Views from the Outside

Fiera: Views from the Outside is an acrylic painting by Bony Ramirez. The work is on Bristol paper and mounted onto a wood panel. The painting is square, measuring six feet wide by six feet tall.

This mixed media artwork is also made with colored pencil, soft oil pastel and eight taxidermy butterflies. The background of the painting is a bright and stark cerulean or sky blue. The foreground depicts the top of a coconut palm tree’s brown curved trunk and the spiky green leaves of five palm fronds. The top half of the canvas is filled with the palm fronds and the bottom half shows the top of the palm tree’s trunk. There are two bunches of green coconuts on the left side of the trunk, and one bunch on the right side.

There is a jaguar with a human head suspended within the tree’s fronds. Its legs are wrapped into the top of the tree, and it hangs downwards, stretched across the top half of the composition. Its right paw is propped up against the top of the tree trunk and the jaguar’s head is slightly above the center of the canvas. It hangs just where the trunk meets the palm fronds of the tree.

This creature is orange with big black spots down the spine of its back. The head of the jaguar is that of a human with long brown hair pulled back into a ponytail and bangs swept across the face. It has thick bushy brown eyebrows above wide hazel eyes. Rainbow swirls in its ears resemble the inside of a conch shell. The creature’s face is covered in blood and in its mouth are the fleshy innards of an antelope. The jaguar is holding the parts of the animal with its left paw. The horn of the antelope rises out of the flesh and points upward. A single hooved leg with light brown fur hangs down from the middle to the bottom of the canvas.

On the surface of the canvas there are eight black butterflies in the form of a grid. On the upper half of the image, there are three black butterflies: two on top of the palm fronds and one on the jaguar’s body. In the center, there are butterflies on either side of the dismembered animal’s hoof, while three more float on the bottom of the canvas below the coconut tree.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Chris Ofili: Iscariot Blues

Iscariot Blues belongs to Chris Ofili’s Blue Paintings series, which he began after his move to Trinidad in 2005. Characterized by blue paint layered over silver backgrounds that create an effect reminiscent of moonlight, this series marked a new direction in his work. These paintings require time to appreciate fully, as their details emerge gradually from their monochromatic darkness.

In Iscariot Blues, Ofili blends various elements of Trinidadian culture. The painting features two musicians playing parang (traditional folk music from Trinidad and Tobago) alongside a bobolee—an effigial representation of Judas Iscariot that locals traditionally beat during Good Friday ceremonies. Ofili chose to depict Judas naked to symbolize the disciple’s guilt and regret (and, ultimately, suicide) over betraying Jesus, while he based the musician figures on flat plywood cutouts that he photographed in the village of Lopinot.

Ofili’s blue palette also evokes the “jab-jab,” or “blue devil,” a Trinidadian Carnival character. Masqueraders in this guise coat themselves in blue paint, wear horns and chains, and perform threatening gestures through aggressive dance. Born from resistance to colonial power, this tradition emerged as formerly enslaved people mocked their oppressors. Ofili returned to this potent symbol nine years later in his work Blue Devils (2014). While deeply rooted in Trinidad’s cultural landscape, these blue paintings also invite broader reflection on history, power, and resistance.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Visual description: Iscariot Blues

Iscariot Blues by Chris Ofili is a painting from 2006. It is made with oil and charcoal on linen. It measures about nine feet by six feet. The work is in portrait orientation, meaning that its shortest side runs parallel to the ground.

The painting depicts a hanged figure and two others playing instruments.

The painting is monochromatic, meaning it is composed of one color and its various tones. The background is painted with layers of a washy dark blue. On the top edge of the canvas there are leaves, vines, and branches. They hang and droop toward the bottom of the image. The foliage is black and various shades of dark blue. Underneath them there are two figures playing instruments. Their features are obscured and their skin black. The figure on the left has a striped shirt and is holding what appears to be maracas. The one on the right is sitting down, wearing a solid-colored shirt with a large collar, and holding a stringed instrument that looks like a banjo. To their right is a naked black hanging figure whose skin appears to be mutilated. His face looks upwards toward the sky.

guide

Caribbean Art Highlights

Feedback

We hope you enjoyed this Digital Exhibition Guide!

We appreciate you taking the time to submit feedback to us as we strive to make PAMM as engaging as possible. You may submit your feedback anonymously through this form or by emailing us directly at AppFeedback@pamm.org